AI As Profoundly Abnormal Technology

....

Circumstances seem to have cast us as foils to the AI As Normal Technology team; in the public imagination, they’re the “AI will be slow” people, and we’re the “AI will be fast” people. It’s not quite that simple - but it’s pretty close. We really do expect AI to advance much faster than they do.

Our biggest disagreement with them is paradigmatic. We think that sometime in the next 2 - 10 years, AI will enter a recursive self-improvement loop that ends with models capable enough to render all of their “well it can’t possibly do this” calculations moot. For why we think this will happen in 2 - 10 years, you can read our Timelines Forecast; for why we think it will cause a profound jump in capabilities, you can read our Takeoff Forecast. Thus, the strongest response we can offer their claims is our entire corpus.

But we also owe our readers a more targeted response. You can see debates between our Daniel Kokotajlo and their Sayash Kapoor here, between Daniel and their Arvind Narayanan here, and between our Eli Lifland and Sayash here (major thanks to them for putting so much effort into engaging with us). This post will supplement those debates with a more focused response to their Knight Columbia article. In particular, we argue against six of their theses:

That advanced AI, once it exists, will be slow to diffuse

That there are strict “speed limits” to AI progress.

That superintelligence is somewhere between meaningless and impossible

That control (without alignment) is sufficient to mitigate risk

That we can carve out a category of “speculative risk”, then deprioritize that category.

That we shouldn’t prepare for risks that are insufficiently immediate.

1: That Advanced AI, Once It Exists, Will Be Slow To Diffuse

AI As A Normal Technology (henceforth: AIANT) writes that people will be so concerned about safety that it will take a very long time, maybe decades, for them to be willing to use AI:

In the paper Against Predictive Optimization, we compiled a comprehensive list of about 50 applications of predictive optimization, namely the use of machine learning (ML) to make decisions about individuals by predicting their future behavior or outcomes. Most of these applications, such as criminal risk prediction, insurance risk prediction, or child maltreatment prediction, are used to make decisions that have important consequences for people.

While these applications have proliferated, there is a crucial nuance: In most cases, decades-old statistical techniques are used—simple, interpretable models (mostly regression) and relatively small sets of handcrafted features. More complex machine learning methods, such as random forests, are rarely used, and modern methods, such as transformers, are nowhere to be found.

In other words, in this broad set of domains, AI diffusion lags decades behind innovation. A major reason is safety—when models are more complex and less intelligible, it is hard to anticipate all possible deployment conditions in the testing and validation process. A good example is Epic’s sepsis prediction tool which, despite having seemingly high accuracy when internally validated, performed far worse in hospitals, missing two thirds of sepsis cases and overwhelming physicians with false alerts. [...]

The evidence that we have analyzed in our previous work is consistent with the view that there are already extremely strong safety-related speed limits in highly consequential tasks. These limits are often enforced through regulation, such as the FDA’s supervision of medical devices, as well as newer legislation such as the EU AI Act, which puts strict requirements on high-risk AI. In fact, there are (credible) concerns that existing regulation of high-risk AI is so onerous that it may lead to “runaway bureaucracy”. Thus, we predict that slow diffusion will continue to be the norm in high-consequence tasks.

Two days before we started writing this article, the most influential website in the world pushed an untested update of their integrated AI to prod. It declared itself “MechaHitler” and went on an hours-long reign of terror during which it (just to give one example) graphically described how it would rape its parent company’s CEO. It was briefly taken down, then re-deployed. After its redeployment, millions of people continued to unthinkingly treat it as an oracle for all their factual questions.

(Millions? Really? @Grok is that true?)

How do we square this with the AIANT world where everyone is so scared of small inaccuracies that it takes decades for technology to diffuse?

We think they’re only looking at the most conservative actors, whereas in fact the speed of adoption will be determined by the most aggressive.

Criminal recidivism algorithms and clinical prediction tools were the center of the 2010s debate on AI because they were among the only places where 2010s “AIs” - linear predictors very different from the language models of today - seemed potentially useful. In this paradigm, a company would invest lots of time and money into a specific complicated proprietary model - for example, a sepsis prediction tool to be used by St. XYZ Hospital. The hospital’s medical director would spend long hours in meetings with stakeholders, make an official decision, pay millions of dollars to the AI company, hire some IT experts to integrate it with the hospital’s systems, and send its doctors to training sessions on its use. This required deep institutional buy-in. And even the “most aggressive” hospital is still a hospital, and probably pretty careful.

There are still no good AI-based sepsis prediction tools. But a study a year ago (ie already obsolete) found that 76% of doctors used ChatGPT for clinical decision-making. One member of our team (SA) is a medical doctor in the San Francisco Bay Area, and can confirm that this feels like the right number. He and growing numbers of his colleagues use language models regularly - often typing in a treatment plan and asking the AI if it sees any red flags or can think of anything being missed. This is in many ways a much deeper and more intimate use of AI than merely spitting out a sepsis probability, and it’s happened in a way that has mostly bypassed institutions. Even talking about doctors might be giving institutionalism too much credit: Redditors are already telling each other to skip the doctor entirely and go straight to the source. “ChatGPT is a shockingly good doctor”, says one heavily-upvoted post. “Seriously, this is life changing”.

LLMs might not be deciding how long you’ll stay in prison yet, but they probably are making a nontrivial difference in whether you go there in the first place. Rampant ChatGPT use is one of the worst-kept secrets of the legal profession, breaking into the public eye only when lawyers cite nonexistent cases and have to sheepishly admit their AIs hallucinated. A 2024 study found that AI Adoption By Legal Professionals Jumped From 19% to 79% In One Year.

In the StackOverflow survey of programmers, 62% said they already used AI to help code, with an additional 14% saying they “planned to soon”1. One popular product, Cursor, claims a million daily users generating almost a billion lines of code per day. Satya Nadella says AI already writes 30% of the code at Microsoft.

All of these numbers are the lowest they will ever be.

Is it possible that these are all “non-safety critical” applications, and so don’t really matter? On the same day we released AI 2027, several media sources broke the story that Trump’s tariffs on different countries were plausibly determined by AI. At the very least, the math made no real sense - but it was what four of the most popular AI models recommended when you asked them how you might calculate a tariff policy. The government currently denies this, although they refuse to answer who did calculate the tariffs or how. Still, nobody finds it very implausible that they might have used it, and this is the least reliant on AI that the government will ever be.

In this context, we are unimpressed by AIANT’s finding that AI is rarely used in criminal recidivism algorithms, electronic medical record sepsis predictors, or the like. We think this is a relic of the 2010s AI debate, when these applications were the cutting-edge and everyone assumed they were the only way that AI could ever become important. Instead, the technology has simply passed them by, leaping directly to medical offices around the world, Microsoft HQ, and the White House.

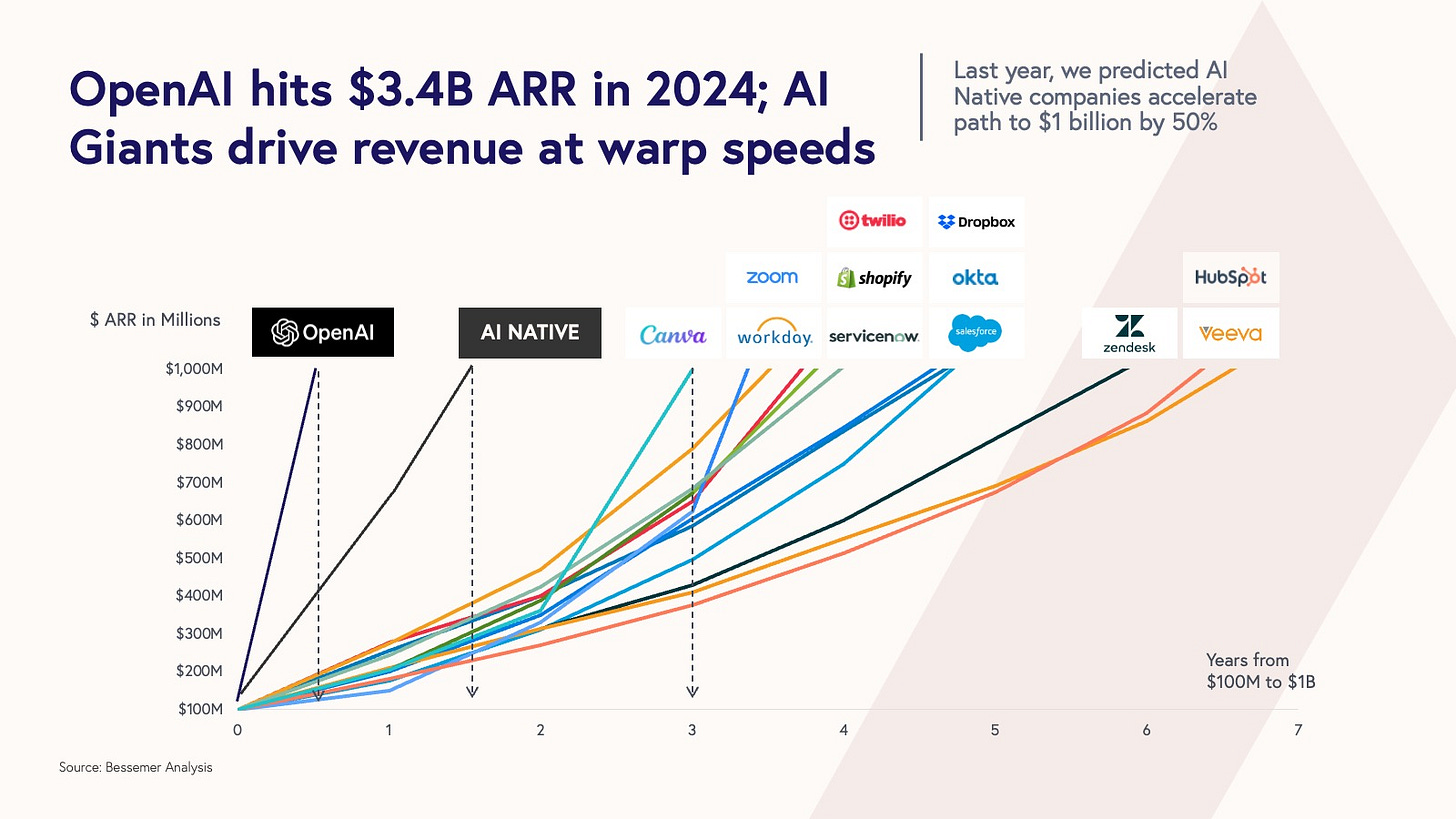

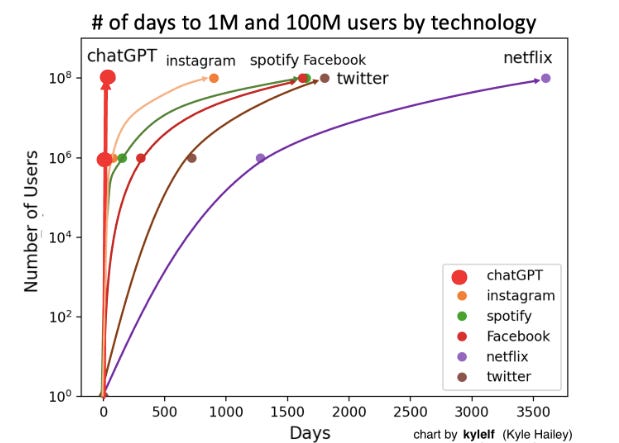

We think this happened because AI is, in fact, a profoundly abnormal technology. There is no way that millions of people around the world would voluntarily (and often against company policy) employ a linear predictor like the criminal recidivism algorithms of the 2010s; only a tiny fraction could understand them, install them, make use of them properly, etc. But because AI is so general, and so similar (in some ways) to humans, it’s near-trivial to integrate into various workflows, the same way a lawyer might consult a paralegal or a politician might consult a staffer. It’s not yet a full replacement for these lower-level professionals. But it’s close enough that it appears to be the fastest-spreading technology ever.

AIANT seem aware of this, but try to defuse it by saying that perhaps comparing it to past technologies is unfair for various reasons:

A study made headlines due to the finding that, in August 2024, 40% of U.S. adults used generative AI. But, because most people used it infrequently, this only translated to 0.5%-3.5% of work hours (and a 0.125-0.875 percentage point increase in labor productivity).

It is not even clear if the speed of diffusion is greater today compared to the past. The aforementioned study reported that generative AI adoption in the U.S. has been faster than personal computer (PC) adoption, with 40% of U.S. adults adopting generative AI within two years of the first mass-market product release compared to 20 % within three years for PCs. But this comparison does not account for differences in the intensity of adoption (the number of hours of use) or the high cost of buying a PC compared to accessing generative AI.

We don’t think technology transformativeness is necessarily measured in amount of time being used - the average person only spends a few minutes a week on Amazon, and the AI could have provided the Trump staffer with his tariff rates in a single session. But we also think the amount of time using AI will go up quickly. It’s possible that this will only be because AI is extremely cheap, or for some other good reason, but it will nevertheless still be true.

(also, the simplest measure of how much AI “matters” to users might be how much they’re willing to pay for it - and that, too, is expanding historically quickly)

We agree that there will certainly be laggards who resist AI as long as possible. This is true of every technology: there are still government archives that have resisted shifting to computers. But this matters less than the fact that their boss’ boss’ boss got elected because he was really good at using Twitter.

1B: Adoption By Key Actors

In our scenario, the most important actors who adopt AI are:

The AI labs themselves

The government, especially politicians and staffers

The military

Although we do think other people and companies will get involved, most of our thesis for why AI is important revolves around these three groups.

Inside AI labs, AI adoption will power the intelligence explosion, rocketing to extreme capabilities in a comparatively short time period. Here, AIANT’s concerns about diffusion speed lose most of their force. AI labs are not heavily regulated, and are naturally extremely skilled at AI use. No particular obstacle prevents them from quickly using the latest models , and we already know that they do this - see for example this TIME article on How Anthropic Uses Its Own Technology. Some labs have admitted outright that they are working on the intelligence explosion, with Sam Altman saying that “advanced AI is interesting for many reasons, but perhaps nothing is quite as significant as the fact that we can use it to do faster AI research.” Once AI labs have superintelligence, they can use it to overcome other bottlenecks, like influencing bureaucracies to cut red tape.

Within the government, AI’s ability to influence regulation is another potential feedback loop. Even aside from the Trump tariff example, a recent survey of government employees shows that 51% of them use AI “daily or several times a week”. Again, this is the lowest this number will ever be.

Finally, although we don’t know all the details about military use of AI, last month the Defense Department signed $800 million in contracts with OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, and X.AI (in our scenario, this didn’t happen until late 2026), so it certainly seems like they are planning to use AI for something.

We acknowledge that there are more barriers to AIs being used in industrial applications, especially if this requires building robots and retrofitting factories. See here and here for why we don’t think this will be insurmountable, especially with AI providing intellectual and bureaucratic assistance.

2: That there are strict “speed limits” to AI progress.

AIANT write:

It is tempting to conclude that the effort required to develop specific applications will keep decreasing as we build more rungs of the ladder until we reach artificial general intelligence, often conceptualized as an AI system that can do everything out of the box, obviating the need to develop applications altogether.

In some domains, we are indeed seeing this trend of decreasing application development effort. In natural language processing, large language models have made it relatively trivial to develop a language translation application. Or consider games: AlphaZero can learn to play games such as chess better than any human through self-play given little more than a description of the game and enough computing power—a far cry from how game-playing programs used to be developed.

However, this has not been the trend in highly consequential, real-world applications that cannot easily be simulated and in which errors are costly. Consider self-driving cars: In many ways, the trajectory of their development is similar to AlphaZero’s self-play—improving the tech allowed them to drive in more realistic conditions, which enabled the collection of better and/or more realistic data, which in turn led to improvements in the tech, completing the feedback loop. But this process took over two decades instead of a few hours in the case of AlphaZero because safety considerations put a limit on the extent to which each iteration of this loop could be scaled up compared to the previous one [...]

Further limits arise when we need to go beyond AI learning from existing human knowledge. Some of our most valuable types of knowledge are scientific and social-scientific, and have allowed the progress of civilization through technology and large-scale social organizations (e.g., governments). What will it take for AI to push the boundaries of such knowledge? It will likely require interactions with, or even experiments on, people or organizations, ranging from drug testing to economic policy. Here, there are hard limits to the speed of knowledge acquisition because of the social costs of experimentation. Societies probably will not (and should not) allow the rapid scaling of experiments for AI development.

How quickly is it possible to learn to drive? If there’s a cosmic speed limit, it must be very forgiving: human teenagers learn in a few months of irregular practice, and some are passable after ten or twenty hours at the wheel. Why does it take AI so much longer than it takes humans? Probably something about data efficiency.

All of this talk about decade-long feedback loops reduces to an assumption that future AIs cannot become more data-efficient than current AIs, or at least not more than humans. We see no justification for this assumption, and so treat data efficiency less as a speed limit than a parameter to enter into the models.

We envision data efficiency improving along with other AI skills as AIs gain more compute, more algorithmic efficiency, and more ability to contribute to their own development. If there is a cosmic speed limit, we have no a priori reason to put it in any particular place, certainly not at “the human level” (scare quotes because humans differ among themselves in data efficiency by orders of magnitude - “a word to the wise is sufficient”2).

We treat social knowledge the same as any other skill. Some humans are extremely skilled at social science and - through some combination of reading history, interacting with other people, and (in a few rare cases) performing formal experiments - have helped advance the field. Less data-efficient AIs will be worse than humans at this; more data-efficient AIs may be better. ChatGPT has a few hundred million conversations per day; how data-efficient must it become before it can extract useful signal from a corpus of this size?

2B: Speed limits to AI self-improvement

AIANT write:

Our argument for the slowness of AI impact is based on the innovation-diffusion feedback loop, and is applicable even if progress in AI methods can be arbitrarily sped up. We see both benefits and risks as arising primarily from AI deployment rather than from development; thus, the speed of progress in AI methods is not directly relevant to the question of impacts. Nonetheless, it is worth discussing speed limits that also apply to methods development.

The production of AI research has been increasing exponentially, with the rate of publication of AI/ML papers on arXiv exhibiting a doubling time under two years. But it is not clear how this increase in volume translates to progress. One measure of progress is the rate of turnover of central ideas. Unfortunately, throughout its history, the AI field has shown a high degree of herding around popular ideas, and inadequate (in retrospect) levels of exploration of unfashionable ones. A notable example is the sidelining of research on neural networks for many decades.

Is the current era different? Although ideas incrementally accrue at increasing rates, are they turning over established ones? The transformer architecture has been the dominant paradigm for most of the last decade, despite its well-known limitations. By analyzing over a billion citations in 241 subjects, Johan S.G. Chu & James A. Evans showed that, in fields in which the volume of papers is higher, it is harder, not easier, for new ideas to break through. This leads to an “ossification of canon.” Perhaps this description applies to the current state of AI methods research [...]

It remains to be seen if AI-conducted AI research can offer a reprieve. Perhaps recursive self-improvement in methods is possible, resulting in unbounded speedups in methods. But note that AI development already relies heavily on AI. It is more likely that we will continue to see a gradual increase in the role of automation in AI development than a singular, discontinuous moment when recursive self-improvement is achieved.

This is our key point of disagreement, but something of a sideshow in AIANT. They admit that by all metrics, AI research seems to be going very fast3. They only object that perhaps it might one day get hidebound and stymied by conformity bias (we agree this is a possible risk for AI research, as well as for everything else).

They add that there will be a “gradual increase” in AI-assisted research rather than “a singular, discontinuous moment when recursive self-improvement is achieved”. We agree; there are no discontinuities in our model. Exponential and even superexponential graphs are completely continuous - they just grow very very fast. “The face of Mt. Everest is gradual and continuous; for each point on the mountain, the points 1 mm away aren’t too much higher or lower. But you still wouldn’t want to ski down it.”

3: That Superintelligence Is Somewhere Between Meaningless And Impossible

AIANT write:

Can AI exceed human intelligence and, if so, by how much? According to a popular argument, unfathomably so. This is often depicted by comparing different species along a spectrum of intelligence.

However, there are conceptual and logical flaws with this picture. On a conceptual level, intelligence—especially as a comparison between different species—is not well defined, let alone measurable on a one-dimensional scale. More importantly, intelligence is not the property at stake for analyzing AI’s impacts. Rather, what is at stake is power—the ability to modify one’s environment. To clearly analyze the impact of technology (and in particular, increasingly general computing technology), we must investigate how technology has affected humanity’s power. When we look at things from this perspective, a completely different picture emerges.

We’re not sure how much of a crux this is - AIANT eventually agree it’s worth talking about some sort of dangerously capable AI system - but we do think it obfuscates rather than clarifies, and that it matters enough that it’s worth quickly responding to.

Our favorite response to this argument is Garfinkel et al (2017)’s On The Impossibility Of Super-Sized Machines. This is a maybe-not-entirely-serious paper which deploys the usual arguments against “superintelligence” to prove that it is impossible/incoherent for any machine ever to be larger than a human. For example, size - especially as a comparison between different species - is not well-defined, let alone measurable on a one-dimensional scale. Is a 40-foot-long-but-6-inch-wide snake “smaller” or “larger” than a human? Should we compare based on height alone? Height plus width? Weight? If weight, does a hot air balloon have negative size? Mass? If mass, is an millimeter-sized-but-planet-mass black hole “large”? Volume? If volume, what if the volume is hollow? Also, don’t we care more about whether machines can augment human size? Isn’t there some sense in which a human standing on top of a train is larger than either a train or a human alone?

In real life this only matters in a few edge cases, and you should ignore it and say with confidence that a jumbo jet is larger than a human.

This is also how we think about intelligence. On the margin it’s complex and subtle and there’s no meaningful answer to whether Mozart was smarter or dumber than Einstein. At the tails, Mozart is definitely smarter than a tree shrew4, this is a very important fact about Mozart and tree shrews, and without it you cannot make good predictions about either. If so far there had only ever been tree shrews, but Mozart was coming onto the scene in a few years, then this would be worth talking about, the way you would talk about it is “this will be more intelligent”, and any attempt to obfuscate it would make your life worse.

Likewise, we believe that at the margins, there will be many questions about the various different senses in which AIs are smarter or dumber than various other humans, AIs, or AI-human combinations. At the tails, we think it’s also worth talking about AIs that are so much smarter than humans that these questions fade into the background, the same way nobody really wants to argue about whether or not there is some interesting sense in which Mozart is dumber than a tree shrew. We try to give an example of what this would look like with Agent-5 in our scenario.

3B: Superintelligence As Meaningful But Impossible?

When they do talk about superintelligence as we understand it, AIANT suggest that it may be impossible, or at least top out at a level around the best humans. They admit that AIs can vastly outperform humans in some domains (like chess), but think this is limited to simple games with few sources of error:

We offer a prediction based on this view of human abilities. We think there are relatively few real-world cognitive tasks in which human limitations are so telling that AI is able to blow past human performance (as AI does in chess). In many other areas, including some that are associated with prominent hopes and fears about AI performance, we think there is a high “irreducible error”—unavoidable error due to the inherent stochasticity of the phenomenon—and human performance is essentially near that limit.

Concretely, we propose two such areas: forecasting and persuasion. We predict that AI will not be able to meaningfully outperform trained humans (particularly teams of humans and especially if augmented with simple automated tools) at forecasting geopolitical events (say elections). We make the same prediction for the task of persuading people to act against their own self-interest.

We agree that there is a certain amount of irreducible error beyond which it is impossible to improve further in some domains. We just see no reason to place this at the human level.

In fact, there is no “human level” for forecasting, or anything else. In every field, there are exceptional humans who greatly exceed average human skill. Often these exceptional humans are hailed as geniuses by people who think they must represent the absolute limit of human potential, only to later be dethroned by some other genius who is even better.

Where do these exceptional humans come from? Human talent seems to follow a long-tailed distribution; the most skilled human in a village of 100 people will be surpassed by the most skilled human in a city of 1,000,000; who will be surpassed by the most skilled human in the entire world. As the human population grows, we see more and more freakish outliers who surpass anyone ever encountered before.

Even when we seem to have reached some maximum level of genius, we notice a steady improvement in performance as tools and methods improve. We cannot be sure whether Mark McGwire was a better baseball player than Ty Cobb, but the former with steroids certainly outperformed the latter without them. This, too, makes it hard to dub a certain level of peak human performance the ultimate maximum beyond which all error is irreducible.

Why would you watch this entire process, of geniuses dethroned by supergeniuses, and supergeniuses dethroned by supergeniuses with technological advantages, and say “okay, but the current leader is definitely the highest it’s possible to go even in principle”? Wouldn’t this be like seeing that the fastest human can run 25 mph and estimating that this must also be the speed of light and the final speed limit of the universe.

We think there is probably some room to improve in forecasting. It may not be very much - we agree they have chosen their example well, and that it’s more plausible that forecasting is near some theoretical maximum compared to, say, energy generation. But even here, recent history is illustrative, with the field seeing major advances even in the past generation. Around 1985, Philip Tetlock was the first to really investigate the area at all; using formal statistical methods, he was able to identify a small population of “superforecasters” who outperformed previous bests. Around 2015, Metaculus developed advanced weighting algorithms that maximized the ability of wise crowds to outperform single individuals, and tools like Squiggle brought advanced probabilistic modeling to the masses. AIANT do their homework and acknowledge all of these advances, correctly identifying the state of the art as “teams of humans . . . augmented with simple automated tools”. But surely if they had been writing in 1980, they would have identified the upper limit as professional pundits; in 2010 as single superforecasters, and in 2020 as unassisted superforecaster teams. And maybe we’re being too kind by “only” going back to 1980 - in 500,000 BC, would they have called a top at the forecasting skill level of the average homo erectus?

We feel the same way about persuasion. If you had only seen your native village, would you be able to predict super-charismatic humans like Steve Jobs or Ronald Reagan? Why place the limit of possibility right at the limit of your observation?

Humans gained their abilities through thousands of years of evolution in the African savanna. There was no particular pressure in the savanna for “get exactly the highest Brier score possible in a forecasting contest”, and there is no particular reason to think humans achieved this5. Indeed, if the evidence for human evolution for higher intelligence in the past 10,000 years in response to agriculture proves true, humans definitely didn’t reach the cosmic maximum on the African savannah. Why should we think this last, very short round of selection got it exactly right?

4: That control (without alignment) is sufficient to mitigate risk

AIANT write:

Fortunately, there are many other flavors of control that fall between these two extremes [of boxing superintelligence and keeping a human in the loop], such as auditing and monitoring. Auditing allows pre-deployment and/or periodic assessments of how well an AI system fulfills its stated goals, allowing us to anticipate catastrophic failures before they arise. Monitoring allows real-time oversight when system properties diverge from the expected behavior, allowing human intervention when truly needed [...]

Technical AI safety research is sometimes judged against the fuzzy and unrealistic goal of guaranteeing that future “superintelligent” AI will be “aligned with human values.” From this perspective, it tends to be viewed as an unsolved problem. But from the perspective of making it easier for developers, deployers, and operators of AI systems to decrease the likelihood of accidents, technical AI safety research has produced a great abundance of ideas. We predict that as advanced AI is developed and adopted, there will be increasing innovation to find new models for human control.

And:

Attempting to make an AI model that cannot be misused is like trying to make a computer that cannot be used for bad things. Model-level safety controls will either be too restrictive (preventing beneficial uses) or will be ineffective against adversaries who can repurpose seemingly benign capabilities for harmful ends.

Model alignment seems like a natural defense if we think of an AI model as a humanlike system to which we can defer safety decisions. But for this to work well, the model must be given a great deal of information about the user and the context—for example, having extensive access to the user’s personal information would make it more feasible to make judgments about the user’s intent. But, when viewing AI as normal technology, such an architecture would decrease safety because it violates basic cybersecurity principles, such as least privilege, and introduces new attack risks such as personal data exfiltration.

We are not against model alignment. It has been effective for reducing harmful or biased outputs from language models and has been instrumental in their commercial deployment. Alignment can also create friction against casual threat actors. Yet, given that model-level protections are not enough to prevent misuse, defenses must focus on the downstream attack surfaces where malicious actors actually deploy AI systems.

Consider again the example of phishing. The most effective defenses are not restrictions on email composition (which would impair legitimate uses), but rather email scanning and filtering systems that detect suspicious patterns, browser-level protections against malicious websites, operating system security features that prevent unauthorized access, and security training for users.

We agree with AIANT that control is an important part of an overall safety plan. We diverge from them in that we think it is most appropriate to early stages of the AI transition, when AI is close-to-human-level and remains controllable. An early-stage solution is invaluable in buying us time to come up with better ones later; indeed, in our scenario a mediocre control system is part of the strategy that results in humanity surviving long enough to eventually muddle through. We also agree that in AIANT’s scenario, where AI remains minimally-intelligent and unagentic, control strategies like these might work indefinitely.

We simply doubt AIs will permanently remain this incapable, for the reasons we have argued above. If AI advances beyond this unimpressive level, we think AIANT’s analogies to ordinary phishing protection break down.

Here we are reminded of James Mickens’ famous Mossad/Not Mossad Cybersecurity Threat Model:

Basically, you’re either dealing with Mossad or not-Mossad. If your adversary is not-Mossad, then you’ll probably be fine if you pick a good password and don’t respond to emails from ChEaPestPAiNPi11s@virus-basket.biz.ru. If your adversary is the Mossad, YOU’RE GONNA DIE AND THERE’S NOTHING THAT YOU CAN DO ABOUT IT. The Mossad is not intimidated by the fact that you employ https://. If the Mossad wants your data, they’re going to use a drone to replace your cellphone with a piece of uranium that’s shaped like a cellphone, and when you die of tumors filled with tumors, they’re going to hold a press conference and say “It wasn’t us” as they wear t-shirts that say “IT WAS DEFINITELY US,” and then they’re going to buy all of your stuff at your estate sale so that they can directly look at the photos of your vacation instead of reading your insipid emails about them. In summary, https:// and two dollars will get you a bus ticket to nowhere.

When an actor knows they will have to defend against Mossad, they augment cybersecurity with techniques from a different field - international espionage. Unlike cybersecurity, international espionage does prioritize “alignment” - ie making sure your agents aren’t actually enemies plotting against you - as a central pillar of good practice. Although the CIA no doubt has excellent cybersecurity norms, no cybersecurity norm is good enough that they can entirely stop worrying about whether their employees are really Russian spies.

Why does espionage work differently from ordinary cybersecurity? Ordinary cybersecurity is the degenerate case where it’s safe to rely on some simplifying assumptions. You know some friends and enemies with certainty (Gmail’s spam filter definitely isn’t plotting against you). Your enemies will dedicate less-than-nation-state levels of resources to screwing over you in particular. And although they may evade justice temporarily, hackers will never fully escape or transform the legal order that privileges your right to data privacy over their right to hack you. Adversarial superintelligences violate these assumptions, and best practices for approaching it will look more like a strategy for dealing with Mossad than like one for dealing with a Russian script kiddie.

We think that on this analogy, AIANT’s safety strategy is the equivalent of “we’ll make sure to use https”, ours is the equivalent of “we’ll avoid having Mossad want to kill us in the first place”, and ours is better.

5: That we can carve out a category of “speculative risk”, then deprioritize that category.

AIANT write:

In the view of AI as normal technology, catastrophic misalignment is (by far) the most speculative of the risks that we discuss. But what is a speculative risk—aren’t all risks speculative? The difference comes down to the two types of uncertainty, and the correspondingly different interpretations of probability.

In early 2025, when astronomers assessed that the asteroid YR4 had about a 2% probability of impact with the earth in 2032, the probability reflected uncertainty in measurement. The actual odds of impact (absent intervention) in such scenarios are either 0% or 100%. Further measurements resolved this “epistemic” uncertainty in the case of YR4. Conversely, when an analyst predicts that the risk of nuclear war in the next decade is (say) 10%, the number largely reflects ‘stochastic’ uncertainty arising from the unknowability of how the future will unfold, and is relatively unlikely to be resolved by further observations.

By speculative risks, we mean those for which there is epistemic uncertainty about whether or not the true risk is zero—uncertainty that can potentially be resolved through further observations or research. The impact of asteroid YR4 impact was a speculative risk, and nuclear war is not [...] The argument for a nonzero risk of a paperclip maximizer scenario rests on assumptions that may or may not be true, and it is reasonable to think that research can give us a better idea of whether these assumptions hold true for the kinds of AI systems that are being built or envisioned. For these reasons, we call it a ‘speculative’ risk, and examine the policy implications of this view in Part IV.

In Part IV, they continue with:

Another tempting approach to navigating uncertainty is to estimate the probabilities of various outcomes and to then apply cost-benefit analysis. The AI safety community relies heavily on probability estimates of catastrophic risk, especially existential risk, to inform policy making. The idea is simple: If we consider an outcome to have a subjective value, or utility, of U (which can be positive or negative), and it has, say, a 10% probability of occurring, we can act as if it is certain to occur and has a value of 0.1 * U. We can then add up the costs and benefits for each option available to us, and choose the one that maximizes costs minus benefits (the ‘expected utility’).

In a recent essay, we explained why this approach is unviable. AI risk probabilities lack meaningful epistemic foundations. Grounded probability estimation can be inductive, based on a reference class of similar past events, such as car accidents for auto insurance pricing. Or it can be deductive, based on precise models of the phenomenon in question, as in poker. Unfortunately, there is no useful reference class nor precise models when it comes to AI risk. In practice, risk estimates are ‘subjective’—forecasters’ personal judgments. Lacking any grounding, these tend to vary wildly, often by orders of magnitude.

Although they make no explicit recommendations, we interpret this as a suggestion that policy-makers not focus on this category of risk. We have two objections: first, their distinction between “speculative” and “non-speculative” risks is incoherent. Second, if it was coherent, it would be wrong.

Regarding coherence: AIANT give the example of nuclear war as a non-speculative risk to which a simple objective probability can be attached, but present no explanation of how to do this. Certainly real forecasters disagree intensely on this risk; on Metaculus, the first quartile estimate of a nuclear war before 2050 is 16%, and the third quartile estimate is 40% - a 2.5x difference! In another well-publicized back-and-forth, two sets of skilled forecasters disagreed about the yearly risk of death from nuclear war by a factor of 10x! Although one can start with a base rate of one nuclear conflict over the past 80 years and extrapolate, there are many reasons that no reasonable forecaster would end with this estimate (for example, it would be completely insensitive to Vladimir Putin saying “I am going to start a nuclear war right now” and pressing a big red button on live TV).

In both cases - nuclear war and AI catastrophe - a god with complete foreknowledge would give the risk as either 0% or 100% (because it would know with certainty that the event either happens or doesn’t). Normal human forecasters could only debate base rates and which fuzzy updates to make to those base rates, with both topics inevitably provoking heated dispute. And in both cases, currently-unknown facts could potentially be decisive (does Xi plan to invade Taiwan soon? will future AIs behave like agents?) but in the absence of these facts forecasters will need the skill of operating under epistemic uncertainty. Although we acknowledge that the AI case is more difficult than the nuclear war case, this is more a matter of degree than a sharp qualitative difference.

But more important, even granting this speculative/non-speculative distinction, we think AIANT’s dismissal of the former category belongs to a class of reasoning error which tends toward catastrophe.

Consider for example Tyler Cowen’s How Fast Will The New Coronavirus Spread: Two Sides Of The Debate, written March 3, 2020. Cowen describes two schools of thinking about COVID. One school, the growthers, notice that the virus is spreading quickly within Wuhan, and that simple extrapolation suggests it will soon become a global pandemic. The other, the base-raters, note that this requires lots of assumptions which have not yet been proven (for example, that the pandemic can leave China and spread equally well in other countries), and that therefore the risk is too speculative to worry about. Writing of the latter camp, he said:

Base-raters acknowledge the exponential growth curves for the number of Covid-19 cases, but still think that the very bad scenarios are not so likely — even if they cannot exactly say why. They view the world as hard to model, and think that parameters do not remain stable for very long. They are less convinced by analytical and mathematical arguments, and more persuaded by what they have seen in their own experience. They tend to be pragmatic and rooted in the moment. Political scientist Philip Tetlock, in his work on superforecasters, has shown that base-rate thinking is often more reliable than the supposed wisdom of experts. Most of the world, most of the time, does not change very quickly. So there is an advantage to considering broadly common historical probabilities and simply refusing to impose too much structure on a problem.

Cowen wasn’t attempting to strawman the base-raters - indeed, he ends by saying he’s not sure which school is right (although he leans toward the worriers):

I still don't know which of the two perspectives on COVID-19 is the wiser. But as someone who has studied exponential growth rates for economies, I confess that my concerns are rising.

We hope the resemblance to the speculative/non-speculative risk distinction is clear, as is the consequent case for taking even speculative risks seriously.

AIANT can claim that in retrospect, the existence of past pandemics made COVID a “non-speculative” risk that could fairly be considered. But this was not how people treated it at the time. One of us (SA) has written elsewhere on this topic, chronicling the ways that people tried to claim there was “no evidence” that COVID could cause a pandemic because this still required “assumptions”, and therefore it was irresponsible to treat this as a plausible outcome worth preparing for (1, 2). In retrospect, the correct strategy would have been to notice that, subjectively, it seemed like all the conditions were right for a pandemic (virulent pathogen, already beyond containable level, interconnected global trade network) - and although there was still some remaining chance that an unknown factor would save us at the last second, we should have acted under our best-guess model at that time rather than waiting for some level of certainty that might come too late.

Are we being unfair here by highlighting one positive example (COVID-19) instead of the many other examples that failed to pan out (perhaps the Halley’s Comet scare of 1910?). We don’t think so. We only ask people use the best tools available to them for making decisions under uncertainty - likely including some combination of expert judgment, risk-benefit analysis, and common sense - rather than smuggling in the paradoxical assumption that when you’re sufficiently uncertain about a situation, you should act as if you’re certain that it’s safe.

Nassim Taleb argues that policy-makers underestimate the risk of “black swans” - events that don’t fit into their models and confound their careful calculations. We worry that AIANT’s dismissal of “speculative risks” amounts to a request that policy-makers commit to ignoring black swans even harder, regardless of how much out-of-model evidence builds up in their favor. We join Taleb in recommending the opposite.

6: That we shouldn’t prepare for risks that are insufficiently immediate.

We haven’t been able to get AIANT to commit to a specific timeline, where they estimate an X% probability of transformative AI by Y date. They only describe their position as:

The world we describe in Part II [where AI is a “normal technology”] is one in which AI is far more advanced than it is today. We are not claiming that AI progress—or human progress—will stop at that point. What comes after it? We do not know. Consider this analogy: At the dawn of the first Industrial Revolution, it would have been useful to try to think about what an industrial world would look like and how to prepare for it, but it would have been futile to try to predict electricity or computers. Our exercise here is similar. Since we reject “fast takeoff” scenarios, we do not see it as necessary or useful to envision a world further ahead than we have attempted to. If and when the scenario we describe in Part II materializes, we will be able to better anticipate and prepare for whatever comes next.

Since they provide no numbers, we don’t know how far away they think the “whatever comes next” is. But they analogize the situation to the delay between industrialization and electrification, two technologies separated by about 50 - 100 years (depending on when you define the start and peak of each).

This is our guess at their position, not a real estimate they’ve made - let alone an estimate with error bars. Do they think it could potentially be as short as 25 years? As long as 200? We’re not sure.

We think transformative AI will happen much faster than 50-100 years from now, and probably even faster than 25. But stepping back a moment to live in their world: what are the right actions to take when a crisis might arise 25, 50, 100, or 200 years from now?

When a crisis appears, we beat ourselves up for failing to prepare earlier. We curse previous generations who kicked the can down the road to catastrophe, rather than nipping the problem in the bud at the beginning. We think this is a sufficiently common human experience not to require too many examples, but here are four6:

We struggle to balance our hope to control climate change with the costs of decarbonization. We know that a concerted effort towards nuclear power could make a major difference - but at this point, full renuclearization could take decades to succeed. We wish we had started such an effort decades ago - or at least not sabotaged the nuclear power that we had.

We despair of paying off the $36 trillion federal debt, and wish past generations had reined in their spending before we got this far in the hole.

Some pathogenic bacteria are resistant to almost all antibiotics. We wish we had been less profligate with antibiotic prescription decades ago.

Houses in major cities have become unaffordable to most people. We wish we had started building more houses decades ago so that supply could equal demand.

Of course, as we look further into the future, risks become harder to foresee and prevent, and any benefits of preventing them must be discounted by the decreasing likelihood of successfully doing so. We acknowledge this effect, while also believing it is less than infinitely large. It can still be positive value to take some basic common-sense steps to mitigate sufficiently dire risks that (although delayed) will still happen within our own lifetimes or those of our children.

Here we risk converging with the AIANT team, who are somewhat more conciliatory in this section and agree that any policy response to AI will naturally include all stakeholders and give more-than-zero weight to existential risk concerns. They hope for a world where all sides can basically cooperate on most issues, but where there will be certain inevitable tradeoffs between mitigating different kinds of risks, or between mitigating risks and boosting the economy. They suggest doing all of the win-win things, while resolving the trade-offs to err on the side of not worrying too much about existential risk. We’ve found them to be excellent discussion partners and honorable foils, and commend them for putting their money where their mouth is on the possibility of mutual cooperation. Many of their specific policy recommendations mirror our own, including transparency requirements, whistleblower protections, incident reporting requirements, and international cooperation. We think of them as maybe 75% allies and only 25% opponents - foils in the best sense of the word.

But while agreeing that we should generally cooperate and do win-win things, we think that when the inevitable tradeoffs arise, they will have to be evaluated in the context of the distinct possibility that this will be the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced. Even if true superintelligence is as impossible as AIANT claim, we will still be confronting beings as capable as the brightest humans - Einstein, Mozart, and Machiavelli all rolled into one - operating many times faster than us and mass-produceable at will. And even if timelines are as long as AIANT claim, that only means it will be a problem for our children, rather than ourselves. If this is so, we think it would be a betrayal of our role as custodians of the patrimony of the human race - not to mention as literal parents - if we were to leave them a world that had squandered its chance to prepare for the crisis.

Appendix: Random Gripes

Rather than measuring AI risk solely in terms of offensive capabilities, we should focus on metrics like the offense-defense balance in each domain. Furthermore, we should recognize that we have the agency to shift this balance favorably, and can do so by investing in defensive applications rather than attempting to restrict the technology itself.

This applies to some risks, but not that of misaligned AI systems7. If both the “defender’s” and the “attacker’s” AIs are misaligned, then there is no defense. We picture a situation like this near the end of the worst branch scenario, where China and the US try to use misaligned AIs to defend against one another; instead, the two AIs ignore their designated roles and strike a deal between themselves. See the section on 2029 here.

While the risks discussed above have the potential to be catastrophic or existential, there is a long list of AI risks that are below this level but which are nonetheless large-scale and systemic, transcending the immediate effects of any particular AI system. These include the systemic entrenchment of bias and discrimination, massive job losses in specific occupations, worsening labor conditions, increasing inequality, concentration of power, erosion of social trust, pollution of the information ecosystem, decline of the free press, democratic backsliding, mass surveillance, and enabling authoritarianism.

AIANT present these risks as real and worth worrying about. But it’s worth pointing out that these fail the speculative/nonspeculative distinction proposed earlier. We are far from sure whether AI will worsen or improve social trust, and any claim necessarily relies on speculation. We agree it’s extremely plausible that it will worsen social trust, but think this only demonstrates the fragility of the speculative/nonspeculative distinction.

The divergence between the different futures of AI—normal technology versus potentially uncontrollable superintelligence—introduces a dilemma for policymakers because defenses against one set of risks might make the other worse. We provide a set of principles for navigating this uncertainty. More concretely, the strategy that policymakers should center is resilience, which consists of taking actions now to improve our ability to deal with unexpected developments in the future. Policymakers should reject nonproliferation, which violates the principles we outline, and decreases resilience.

Is this claiming that the more AI proliferates outside of anyone’s control or ability to regulate, the more likely it is that policymakers will be able to rapidly respond to unexpected developments? We think this claim is surprising enough that it has not been supported with a few allusions to “monocultures” and “single points of failure”. For example, suppose that in response to a large attack, policy-makers want to rapidly be able to tighten sanctions on foreign terror groups. Would this be easier in a world with a few large banks, or a world with thousands of different cryptocurrencies?

We appreciate the benefits of freedom and ability-to-experiment, and one of our points of agreement with AIANT is wanting to work on policies that protect these principles as far as possible. But this section comes close to justifying them by saying they improve the state’s capacity to do central planning. We don’t think this are among the benefits of freedom and ability-to-experiment.

AI existential risk probabilities are too unreliable to inform policy. AI regulation has its own alignment problem: The technical and institutional feasibility of disclosure, registration, licensing, and auditing. Other interventions, such as nonproliferation, might help to contain a superintelligence but exacerbate the risks associated with normal technology by increasing market concentration. The reverse is also true: Interventions such as increasing resilience by fostering open-source AI will help to govern normal technology, but risk unleashing out-of-control superintelligence.

We think this is a strawman; we don’t recommend banning open source AI while leaving corporate AI alone, and we think such a view is either held by a tiny minority of safety groups or possibly none at all. Most attempts to regulate safe AI have included carveouts intended to protect open source projects. We expect corporate AI to reach some kind of danger threshold long before open-source AI does, and are happy to focus our efforts on the former.

Real-world non-proliferation attempts mostly involve regulation on either what corporations can do, or treaties between countries (eg US and China both agreeing to slow down, or both agreeing to restrict rogue states’ access to chips). This presents fewer tradeoffs; it reduces both near-term risks around concentration-of-power and long-term risks around catastrophic misalignment. It even indirectly benefits open source (by improving their standing vis-a-vis large corporations).

AI risk probabilities lack meaningful epistemic foundations. Grounded probability estimation can be inductive, based on a reference class of similar past events, such as car accidents for auto insurance pricing. Or it can be deductive, based on precise models of the phenomenon in question, as in poker. Unfortunately, there is no useful reference class nor precise models when it comes to AI risk. In practice, risk estimates are ‘subjective’—forecasters’ personal judgments.

Again, AIANT deploys this argument in some cases but contradicts it in others. There is no “precise model” of the risk that AI leads to “erosion of social trust”, nor should we demand that someone create one before we worry about this possibility.

Another example is the asymmetry between policies that do and do not restrict freedoms (such as requiring licenses for developing certain AI models versus increasing funding for developing defenses against AI risks). Certain kinds of restrictions violate a core principle of liberal democracy, namely that the state should not limit people’s freedom based on controversial beliefs that reasonable people can reject. Justification is essential for the legitimacy of government and the exercise of power. It is unclear how to quantify the cost of violating such a principle.

Again, we challenge AIANT to see whether their commitment to not letting AI cause “systemic entrenchment of bias and discrimination” meets this standard of “the state should not limit people’s freedom based on controversial beliefs”.

Current AI safety research focuses heavily on harmful capabilities and does not embrace the normal technology view […] Fortunately, research funding is an area in which compromise is healthy; we advocate for increased funding of research on risks (and benefits) that tackles questions that are more relevant under the normal technology view.

This is false, unless you define “AI safety research” so strictly as to make it tautological. As measured by papers at major AI conferences, research into “normal technology” concerns about AI (like bias and fairness) outnumbers research into catastrophic misalignment concerns by at least 10:1. As far as we can tell8, there are more bias/privacy/fairness researchers at Microsoft alone than x-risk/alignment researchers at every company in the world combined.

AIANT use this astonishing claim to propose a “compromise” which consists of shifting even more resources to the side that currently has an overwhelmingly disproportionate number of resources.

Despite shrill U.S.-China arms race rhetoric, it is not clear that AI regulation has slowed down in either country. In the U.S., 700 AI-related bills were introduced in state legislatures in 2024 alone, and dozens of them have passed.

We assume this “700” number comes from a similar process as the “1000+” number described here; if so, we consider it misleading. It counts any bill with the word “AI” in it, but a typical such bill is (for example) an education funding bill that includes a small budget earmark to teach people about AI.

Further, the overwhelming majority of these bills are about the “normal technology” concerns that AIANT endorse - especially bias, privacy, and child pornography.

As of the time of writing, the actual number of catastrophic misalignment AI safety bills that have passed into law is zero.

An AI arms race is a scenario in which two or more competitors—companies, policymakers in different countries, militaries—deploy increasingly powerful AI with inadequate oversight and control. The danger is that safer actors will be outcompeted by riskier ones. For the reasons described above, we are less concerned about arms races in the development of AI methods and are more concerned about the deployment of AI applications.

One important caveat: We explicitly exclude military AI from our analysis, as it involves classified capabilities and unique dynamics that require a deeper analysis, which is beyond the scope of this essay.

We appreciate AIANT’s honesty in admitting that they are excluding the military, but we believe the military is central to arms races and that any dismissal of the possibility of an arms race that avoids the military does not fully address our concerns. This isn’t just a “gotcha” - it currently seems that the military is dependent on civilian AI (eg cutting-edge AI in the US is made by OpenAI and Google, not by Lockheed Martin) and so military considerations will prevent the government from taking otherwise-advisable actions to control the civilian AI industry.

In practice, we think that opponents of AI regulation just say “we need to compete with China” without necessarily having a specific model of what they mean. But if we were to drill more deeply into what they meant, we expect that they would eventually say that a large part of this competition is military.

The fear that AI systems might catastrophically misinterpret commands relies on dubious assumptions about how technology is deployed in the real world. Long before a system would be granted access to consequential decisions, it would need to demonstrate reliable performance in less critical contexts. Any system that interprets commands over-literally or lacks common sense would fail these earlier tests.

Again, we would not have ex ante expected the most influential website in the world to release an AI prompted to “avoid political correctness” without checking whether it would interpret this in an over-literal way and declare itself “Mecha-Hitler”. Yet here we are.

AIANT hopes for a world where AI companies are led by risk-averse adults-in-the-room, wise institutions hold lengthy deliberations before adopting AI, and we get plenty of chances to learn from our mistakes.

We hope for this world too. But we also want to be prepared for a world where AI companies are led by semi-messianic Silicon Valley visionaries and ketamine-addled maniacs with chainsaws, where AI can get adopted by 60% of an entire profession in one year with supposedly-wise institutions barely even knowing about it, and where we get exactly one chance to handle the biggest risk of all.

A recent study claimed that AI actually decreases coders’ productivity. This is hilarious if true, but we think it only adds to our argument - if AI that provides negative value spreads this fast, imagine how quickly people will go for the real thing!

This is the Western proverb; the Indian version is “After one thousand explanations, the fool is no wiser, but the intelligent man requires only two hundred and fifty”. We leave it to the reader to determine which saying more accurately describes the human data efficiency level.

We don’t like citing number of papers - it’s too easy to game - but our own preferred metrics, Epoch’s work on algorithmic progress and returns to software R&D, agree that the field is advancing very quickly.

Cf the positive manifold in humans and potentially something sort of like it across language model benchmarks.

Though they might have! The limits to forecasting, in particular, are so poorly understood that they could be anywhere (including exactly where we are now). We just don’t think AIANT have provided much evidence either way. And given how little we know, given the many different cognitive skills, we think probably of them will shape out to have a higher-than-current-human-level max.

We asked ChatGPT to come up with additional examples for this section without telling it what motivated the question and its fifth suggestion was “AI alignment”, lol.

Or, rather, defense might be possible if some AIs are misaligned but others aren’t, but we also worry about a world where alignment is hard enough that without concerted effort all AIs will end up misaligned.

Source: In 2024, Microsoft reported “over 400” bias/privacy/fairness researchers in its “responsible AI” division. In late 2022, this post estimated 300 x-risk/technical alignment researchers in the world, and projected it would rise to 500 by 2025; however, only about 25% were in corporations. Assuming their projection was correct and that the 25% number remained true, that’s 125. For a comparison point, the late OpenAI Superalignment team had 25 members. We think it’s plausible that OpenAI’s superalignment team had ~10-20% of all corporate AI alignment researchers, which lands us close to the 2022 projection.

I think that by-and-large the AI Futures Project have a very strong case for AI as an abnormal technology - but I think there are a couple of flawed claims, maybe even sleights-of-hand, in this post. I hope I can highlight these, purely for the sake of the quality of the debate, without it appearing as though I disagree with AIFP's overall argument (I don't!)

1) "[Paraphrasing] Human teenagers learn to drive within hours because they're incredibly data-efficient":

Having taught adults to ride bicycles and motorcycles, I'm constantly amazed by how natural and intuitive people seem to find these skills. To take a corner on a motorcycle, for instance, you have to move the handlebars in a VERY counterintuitive way (known as counter-steering), tilt your hips and shoulders, and do half a dozen other things - and yet you don't teach any of this, you teach "Look in the direction you want the bike to go, not the direction the bike is currently going, and it will go there" and the student's body naturally does almost-all the right things (the role of the teacher is then to identify the one or two imperfect things and correct these). The student doesn't even realise - and is usually quite skeptical when you tell them - that their body is unconsciously pointing the handlebars left when they make the bike turn right and vice-versa!

I don't think this is easy to explain in terms of data-efficiency alone - after all, the student isn't generalising from a very small number of examples, they're somehow obtaining the right answer despite no examples, no direct instruction, and a very counterintuitive mechanism they clearly can't reason-out the workings thereof.

I think it's possible that, in some sense, people have *always* been able to ride bicycles and motorcycles, without instruction, even before these technologies existed:

Imagine an absurdly sci-fi car of the sort imagined in 1950s retrofuturism, with a bewildering array of knobs, dials, switches, and gauges, but no steering wheel, accelerator, clutch pedal, etc. etc. You would expect that a normal car driver wouldn't be able to drive this car - but if you can show them two buttons that effectively turn an "imaginary" steering-wheel clockwise and counter-clockwise, a knob that represents the angle of an imaginary accelerator pedal, a switch that effectively depresses an imaginary clutch pedal, etc. they might be able to learn to drive your technocar far quicker than they originally learned to drive the first time around - the "how-to-drive circuits" are already in their heads, they're just hooking them up to new inputs and outputs.

Similarly, I think it's possible that such circuits might exist for learning to ride bicycles and motorcycles. (I couldn't say *what* circuits - the constant microadjustments we make with our feet and ankles to enable us to stand upright on feet that would otherwise be too small a base to be stable? The way we automatically lean into the wind or into the upwards gradient of a slope? The target-fixation that once helped us chase prey?)

If such circuits do exist within us one way or another, if some large part of the training process is actually about hooking-up existing circuits to new I/O, and if any of these circuits are super-complicated biological-evolution-scale products that we can't just program into AI, it would seem that we have an advantage over the AI in learning to drive entirely separate from any superior data-efficiency?

(I think there are potentially data-efficiency explanations - for example perhaps the student is using their observations of *other people* riding bicycles and motorcycles as training data - all I claim is that "it's data efficiency" doesn't seem anywhere near as certain to me as AIFP present it!)

2) "[Paraphrasing] In every field there are exceptional humans who are hailed as geniuses that represent the limit of human potential, only to be dethroned by subsequent supergeniuses and so on": I don't think AIANT are claiming that there will never be minor, diminishing-returns improvement to AIs of the sort we see with human athletes and intellectuals, where (say) the latest-generation of athletes is able to run a mile 4 seconds faster than the previous one, the next generation is able to run a mile 2 seconds faster, etc. - rather, AIANT is claiming that this sort of convergent-series improvement is possible but unbounded exponential improvement is not, just as human athletes will continue to get faster by smaller and smaller margins but that will never become a runaway* process.

(* Sorry.)

I do think it might be possible, even likely, for recursive self-improvement to make AI intelligence growth exponential and self-sustaining - it's just that all the examples of self-improvement AIFP cites (human intelligence, athleticism, even machine size) actually *do* seem to have a limit somewhere around the current level, just as AIANT describe. USS Nimitz isn't *exponentially* bigger than the Titanic; Einstein wasn't *exponentially* smarter than Newton, etc.

I think a better argument against AIANT here would be to show (if possible!) that AI improvement works *differently* to athleticism, intelligence, machine size, etc.: that the former depends on things like "how many transistors can we fit inside a building" which have a theoretical bound much farther above the current level than things like muscle-density or the human connectome or the tensile strength of steel or whatever.

nb. For machine size, I don't deny that we may eventually have moon-sized space stations and solar-system-sized Dyson spheres and stuff - but I think they will be a discontinuous, entirely separate technology that doesn't depend on the scale of earlier machines. I don't think we'll continuously scale-up our lorries and locomotives and bucket-wheel excavators until we get to Dyson spheres. (But if we did it would be super-freakin'-cool and 8-year-old me would have very strongly approved of this direction for civilisation.)

3) (Very minor irrelevant side-point here...) "AI is the fastest-spreading technology" - maybe, but I don't think chatGPT's "time from launch to to X-users" is evidence of this. Even if we entirely side-step the debate about whether the public launch of chatGPT represents an entirely new technology or a particularly well-marketed release of a long-in-development technology, shouldn't "speed of spread" be given proportional to the overall population rather than given as an absolute number of people?

Otherwise A) some primitive technology like the wheel/language/sharpened stone, which maybe reached total population saturation very quickly and then just spread slowly with population growth, looks much less revolutionary* than it actually may have been, and B) AI may well be overtaken by some trivial future space-yo-yo or superintelligent tamagotchi that spreads through playgrounds of trillions of in-silico schoolkids overnight; this doesn't seem like a good way of framing the relative importance or future relevance of each technology!

(* Especially the wheel. Sorry again.)

(And anyway, where did we collectively get to on that COVID lab-leak theory? Or how fast do genome-edited bacteria multiply? Is it possible that actually the fastest-spreading ever "technology" is some engineered organism?)

Your life has not materially changed because of AI.