Early US policy priorities for AGI

Near-term AI policy is confusing, except for these two recommendations

This is a guest post from Nick Marsh, a visiting fellow at Constellation who’s worked closely with AI Futures over the past months. The views within are not necessarily the views of AI Futures as an organization (although most AIFP employees tentatively agree with them). To any adversarial readers who want to dunk on our organizational policy recs, just wait a couple of months. We intend to publish a much more comprehensive “positive vision for AGI”, which will have much juicer targets to criticize.

Trying to figure out which policies might help us prepare for AGI is hard. Some proposals look great at first glance, but do not stand up to scenario scrutiny – tracing through, their effects look messy and confusing, and it’s hard to tell whether they’d help or hinder us going forward.

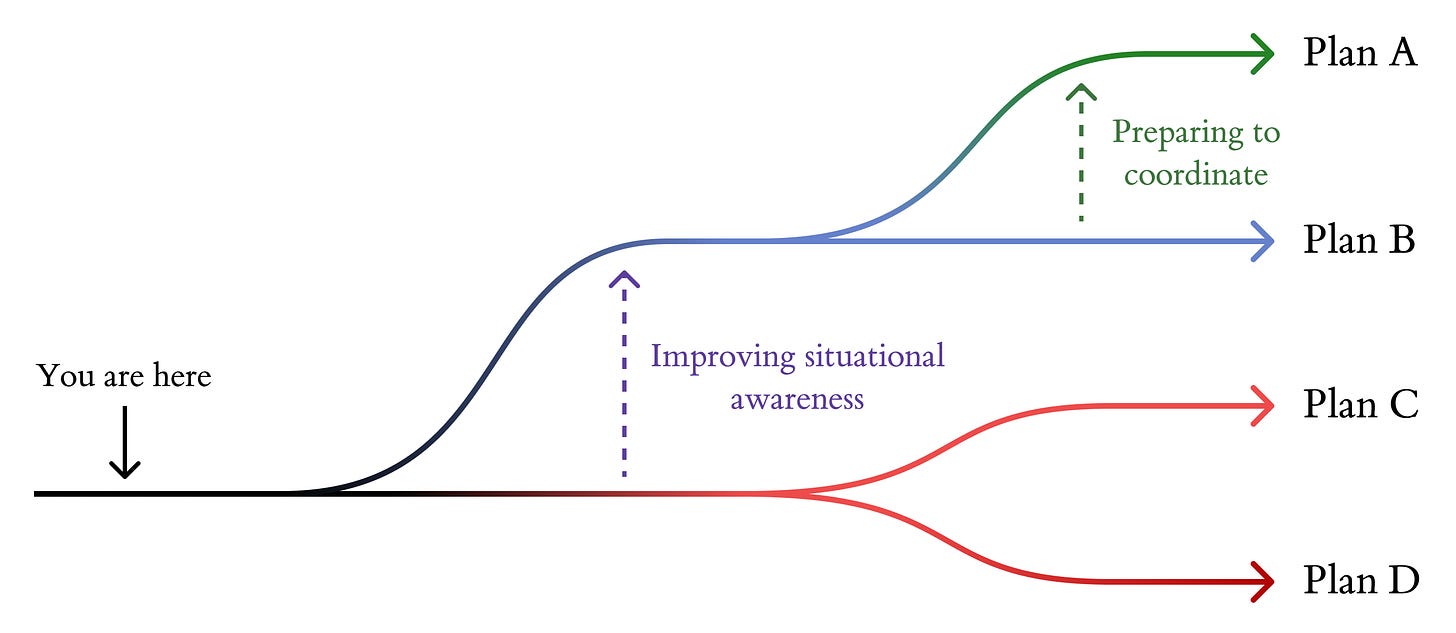

This post is nevertheless an attempt to outline some early policy priorities for the US government that we’re more confident in. (‘Early’ meaning within the next two or three years.) We’ll first discuss a frame – Plans A, B, C, and D – we’ve been using internally to reason about AGI strategy. Then we’ll outline what we think the two core policy priorities for the US are: building situational awareness and preparing to coordinate with adversaries. These policies would help us get into Plan A and B worlds, which are much better.

There are only a few specific policies that we’re entirely comfortable with. This post sketches two — creating a select committee on AGI and implementing sensible chip policy (building a chip registry and an inference-only retrofitting package for data centers) — and concludes with some we tentatively like but are less certain about.

Some background: Plans A, B, C and D

AGI strategy lacks a shared vocabulary. In particular, people discuss fairly lossy abstractions, jumping between potential institution designs (e.g. a Manhattan Project, an Apollo Project, a CERN for AI, Intelsat) without much discussion of how we get to those institutions or what the broader strategic picture would look like, or – maybe most importantly – how we get out of those institutions and into a post-AGI world.

In particular, people sometimes talk past each other regarding plans for approaching transformative AI – there’s some kernel of truth within many of the plans proposed: a Manhattan project to win a race with China; international coordination or a global megaproject; implementing export controls to reduce China’s access to compute; removing export controls to keep China dependent on US chips; MAIM; shutting the whole thing down.

Internally, we’ve been using the terms Plan A, B, C and D to describe different plans that could be pursued to develop AGI (and to categorise scenarios that result from following them). We’ve gotten a lot of mileage out of them in reasoning about AGI strategy.

The below summaries are quite minimal; AI Futures will publish substantially more work in the coming months that uses and expands on this framing.

Plan A (other names: ten year takeoff, managed takeoff, international coordination)

Plan A revolves around an international agreement to slow down takeoff. The parties to this agreement (chiefly the US and China) need to be sure that the other isn’t training models beyond the agreement – so successful execution of Plan A would require verification mechanisms (e.g. chip tracking, on-chip mechanisms, an international chip registry).Plan B (other names: burn the lead)

Plan B requires the US government to be bought-in, but without a strong international agreement. This puts the US in a situation where the goal is to build a robust US capabilities lead (of ≥1 year), building maximum controllable AGIs, and then burn that lead on automated alignment research. This would involve coordinating with willing AGI projects and sabotaging those that aren’t cooperative (e.g. Chinese AGI projects).Plan C (other names: slowdown)

Plan C worlds involve a lab-centric race. There’s limited US government involvement, but AGI development is led by one or more companies who are somewhat concerned about alignment and aim to consolidate as much compute and power as possible to speed up development, in order to buy time to burn on alignment later.Plan D (other names: race)

Plan D involves private labs racing each other to build ASI first – the leading company is not concerned about alignment, but there are a handful of employees who are working on those risks. The government may have some very limited oversight, but ultimately it’s left in the companies’ hands.

Plan A is much better than the other plans

We think it’s far more likely we avoid catastrophic outcomes (avoiding takeover or AI-enabled dictatorship) and end up with a good future in Plan A than Plan B, and similar for Plan B over Plans C and D. To be precise: we think that existential risks from AI or human takeover are at least half as likely in Plan A worlds compared to Plan B worlds.

We think US-China race dynamics in Plan B – where the US government is highly bought in, and significant national resources are dedicated to racing with China – are pretty terrible, compared to worlds where a deal is struck. In particular, it’s unclear how we exit a race:

the US could aim to build and deploy a human-controlled decisive strategic advantage and unilaterally impose its will on China (and the rest of the world);

the US could aim to hand off control to potentially-misaligned superhuman AIs earlier, which might make building a DSA significantly easier;

China could realise that the US is aiming for one of these, and go up the escalation ladder in response, potentially risking WWIII; or

China and the US could strike a deal later – which is likely harder to verify (after years of chip production in an adversarial environment) and negotiated under higher-stakes conditions in a degraded information environment.

Plan B also concentrates power significantly compared to Plan A. It’s easier for leaders to claim that exclusive access to models is required for strategic reasons and that transparency measures would slow down the US, making it easier to amass power.

We think Plan C and D worlds are even worse. Without government oversight, it seems extremely likely that at least one lab rushes towards misaligned superintelligence and we end up with AI takeover. Meanwhile the risk of China freaking out and escalating to war isn’t massively smaller (and possibly not smaller at all) than it is in Plan B.

We want to increase the likelihood we make it into a Plan A world. Secondarily, we want to improve the expected execution of all the plans, given that we think (as of now) Plans C or D are the most likely and Plan A the least likely.

So this post is aiming to outline some early steps that help shift us onto A/B worlds and away from C/D worlds, which we think are significantly more likely to end in doom.

Two core priorities

So, what do the overarching priorities for the next couple of years look like against this background?

First, the US government needs to build situational awareness. As of 2025, there are only a handful of individuals across all three branches of government who understand what’s going on. Almost nobody takes the AI companies seriously when they make clear their intention is to build superintelligence; even a very rudimentary understanding of how AIs are trained hasn’t propagated across the government; very few have tried to wrap their heads around what a takeoff scenario could look like, and what they might do to positively influence one.

Without strong government wakeup (and ability to think through AGI strategy), we remain on-course for Plan C or D worlds, where we leave the future in the hands of lab leaders and race dynamics. Good policymaking requires an alert government.

Second, the US needs to prepare to coordinate internationally. It’s better – and more tractable – to coordinate with China than to try to bully them into submission by racing ahead. But it would be difficult to sign an agreement tomorrow that would give both countries confidence that the other isn’t training models beyond the agreement’s scope.

A small amount of investment into building the institutional, political, and technical capacity to verify that an international agreement is being respected – very small, in light of the stakes of such a negotiation – would widen the bargaining range and move us away from high-risk adversarial dynamics.

Scarier: improving the BATNA

There is another class of policies that might reduce x-risk: actions that improve the best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA) for the US – that is, reduce the risk that racing ends in existential catastrophe. Some of these actions look like improving the US’ ability to race. One example is passing legislation that explicitly permits the federal government to consolidate compute in order to increase the US lead over China, or improving its ability to sabotage adversarial data centers.

Another reason to improve our BATNA is that it must make China’s BATNA worse—at least insofar as the US-China AI race is a zero-sum game. Hence, improving our BATNA raises China’s incentive to strike a deal, making us more likely to reach the Plan A worlds.

We’re generally pretty concerned about these kinds of interventions: they’re higher-risk and escalatory by nature, and might make it less likely we get a deal, both by making racing more attractive to the US and by worsening the security dilemma the US and China are already in.

Other interventions in this camp seem less risky: chiefly those that keep the door open for an agreement during a race, and which improve the epistemics and institutions within the US.

I: Situational awareness

Political will in government to deal with the incoming development of superintelligence is currently extremely low. This is mostly because policymakers do not understand in a visceral, real way that it’s possible that AGI – let alone ASI – is developed within the next few years. And even if they did, the federal government lacks the technical and strategic expertise to build the kind of detailed picture required to pursue sensible policies.

We think that increasing the level of technical and strategic expertise available to the federal government would:

unlock further political will, widening the Overton window and permitting more preparation before crunch time, and

improve strategy and epistemics regarding AGI on the object-level.

We are not saying that members of Congress should go and get PhDs in machine learning. We are, however, saying that to successfully navigate the critical risk period, policymakers will need to understand:

how AIs are trained now, and how training procedures might differ in the future,

the chip supply chain and the geopolitical issues surrounding it,

what takeoff/an intelligence explosion might look like, and why AIs automating AI research is the core problem,

that AGI – let alone superintelligence – could completely break many of our institutions, which rely on human cognition being slow and expensive,

that the alignment problem is potentially hard, and which directions we might pursue to attempt to solve it,

that there are hard technical and geopolitical problems involved in either racing or coordinating with adversaries,

that a significant proportion of AGI development already happens in secret, and that if you don’t ensure that you have oversight soon you may lose your ability to track where the frontier is,

that some good interventions require significant lead time (whereas others can be deferred until later), so you’d better get started on those quickly,

and more.

Leaders need skilled, experienced advisors to get to this point.

A Joint Select Committee for AGI

Congress has some desirable properties as an institution for overseeing AGI development.

For one, it’s composed of many people with differing skillsets, ideologies and values. Insofar as we are concerned by concentration of power – and we think we should be – it seems extremely useful to have a diverse body with access to AGI development that can discuss and legislate in response. Its size also means that there’s more continuity and stability compared to the executive, whereas every four years the priorities and competences of one administration can be replaced with another.

Currently, there are very few congresspeople who are situationally aware regarding AGI development. The vast majority of both houses have little idea of what is coming, and rank risks from AI fairly low on their list of priorities. We – obviously – think that it should be the top priority for lawmakers, and that there’s a significant opportunity to increase Congress’ awareness of the strategic problems associated with AGI development.

Congress as a whole, however, moves very slowly (especially the 119th, which has struggled to pass major legislation so far), and only a few members have the background or interest required to usefully engage with these concerns directly. Moreover, we’d want those members to be able to handle and discuss confidential and classified information, which is hard to do on the open floor.

The existing committee structure is not ideal for this. The natural candidates - Commerce, Science, and Transportation in the Senate and Space, Science and Technology in the House - are huge, overburdened and lack AI-focused subcommittees that could be candidates (and as before, there just aren’t that many members with the required context). AGI is also just a substantially bigger issue that cuts across literally every other committee’s remit.

So we suggest that creating a Joint Select Committee on AGI, a small committee set up with the purpose of investigating the possibility of an intelligence explosion, would be an extremely useful intervention. It could be limited to a period of two years with the explicit function of investigating what the labs are up to and how the US should prepare for potentially rapid AI progress.

An AGI committee could increase Congress’ situational awareness by bringing together the most informed members of both houses, allowing them to hold hearings and issue subpoenas to lab leaders and others (including for confidential information), and giving them an AGI-focused staff to support their operations.

Building talent in the executive

Talent is a major early bottleneck for the executive branch. The table below provides a short description of some talent gaps in the federal government:

Fortunately, there are a wide range of powers available to quickly bring in various kinds of talent, including:

establishing a reserve corps for AI talent (e.g. by using the National Defense Executive Reserve provision in Title VII of the DPA);

directly appointing experts/consultants, or using the IPA to second talent from nonprofits, universities, and other government departments; or

creating an advisory board of civilians with experience in AGI strategy and alignment.

Talent needs are not uniformly distributed throughout the government. In particular, the White House and Commerce (especially CAISI and BIS) would likely differentially benefit from more expertise relative to other departments (for developing strategy and implementing strategy, respectively). Maintaining autonomy and flexibility is a priority for hiring decisions – given that the talent pool will remain limited, trying to squeeze new talent into constrained, functional roles supervised by senior employees lacking AI context would be foolish. (It would also likely deter potential applicants.)

Pitfalls of building talent in the federal government

More generally, there are some predictable failure modes for bringing talent into the executive:

the salaries the federal government can pay employees – even under special hiring authorities – are low compared to what AI talent can attract in the private sector (even at nonprofits);

demands for ideological purity (e.g. only hiring employees from the administration’s party or who share leadership’s exact position on AI) likely lead to poor epistemics;

burdensome managerial structures (and senior leadership who are not thinking clearly about the impacts of AGI) disincentivizes relevant talent from the private sector, used to operating with significant autonomy, from applying;

a significant number of people aiming to position themselves as strong voices on AI strategy either do not believe that superintelligence is a possibility (and so make bad policy proposals), are actively aiming towards ASI regardless of whether it’s aligned, or are self-interested and power-seeking.

These challenges can be overcome by ensuring that you draw on talent from a number of different pools (industry, nonprofits, academia), use your statutory hiring authorities creatively (e.g. seconding from organisations who cover the majority of their salary), and put your best talent in cross-cutting small teams with a wide remit.

There is also a chance that adding talent to the federal government will be net negative, because it could increase the likelihood of bad regulation passing or efforts by the executive branch to consolidate unilateral control over the AI industry and concentrating power. We think that this is, all things considered, a minor negative point – the US remains structurally fairly coup-resistant; much of the concentration-of-power risk comes from lab leaders acting in secret – and that it is still worthwhile to increase the AI competence of the US federal government.

II: Preparing to coordinate

During takeoff, the leading actor will be faced with three options. At any point, they could: (i) race to ASI and hand off trust to a superhuman AI system, (ii) sabotage trailing actors in order to stall for more time, or (iii) make a deal with trailing actors.

The first two options are terrible: handoff probably leads to AI takeover, and sabotage gives you much less time than a deal and plausibly leads to WW3. So perhaps the most robustly good set of interventions involves actively working to keep the possibility of a deal open. We think that these interventions don’t have many negative externalities in Plans A-D, but do significantly increase the likelihood of Plan A occurring.

Start planning explicitly for a (narrow, verifiable) deal as soon as possible. By default, delays make verifying a deal significantly harder: China continues to indigenize its chip supply chain, and there’s simply much more compute in the world to track down. The US government should begin explicitly planning and pushing for an AI related deal. An initial deal would not need to be very intense: we suggest that a good first step is to agree to mutual transparency for AI progress and verification on each other’s large datacenters. This initial agreement lays the bedrock for verifying any future deals that are mutually desirable, while not in and of itself limiting the US strategically.

The US and China should work to generally improve diplomatic relations. Maintaining communication between the White House and Beijing, engage in Track 1 (or 1.5) dialogue, make public cooperative statements, etc.

The US should aim to implement sensible chip policy (discussed below).

Sensible chip policy

There are two obvious ways that a deal like this could fall apart – if:

there’s suspicion that the other side has undisclosed compute stashed away (e.g. in a black site data center, or just as loose compute), allowing it to push beyond the terms of the agreement in the future; or

there’s suspicion that disclosed chips are being used to train models beyond the terms of the agreement.

In response to these concerns, there are two things that the executive branch can immediately begin working on. Respectively,

creating a chip registry – a complete account of the distribution and production of compute, and

preparing a shovel-ready plan to retrofit data centers to be inference-only, including R&D to design and build the required mechanisms and a project to train installers and auditors.

AI Futures will publish more on these two proposals soon – for now, short summaries.

First: a chip registry. The basic notion of a chip registry is extremely simple: a database of AI chips (above a certain threshold for FLOP/s, for instance), tracking their location and owner. It’s fairly straightforward for the US to start a chip registry: they can start by using national technical means, putting the intelligence community to work. It’s fortunate that data centers are (currently) large and run hot; we think that it should be possible for the US to identify a high proportion of the worlds’ compute without the need for international cooperation.

Domestically, it’s even easier – it’s likely possible to use Section 705 of the DPA or other information-gathering authorities to put together a detailed account of compute within the US. Later, the registry can be internationalized or cross-checked with a Chinese compute registry.

Second: a plan to go inference-only. If the only way to ensure that a data center isn’t being used to train a new model is to literally unplug it, you lose a significant amount of value. We should expect leading AI companies to be extremely powerful actors by the time we need to verify a deal, and subsequently expect them to lobby hard against any plans that involve unplugging chips (as this would deprive them of their main revenue source).

Instead, we should allocate public funds (via e.g. DARPA or the CHIPS Act) to incentivize working implementations of an inference-only retrofitting package – a way to ensure that data centers are not being used to train models, instead only permitting running inference on models from an approved list – then do trial runs domestically installing that package on small data centers.

Once a working system is built, regulation (or conditional deregulation) could be used to mandate that new data centers must have fast inference-only retrofitting capacity, and the government would draw up a plan to retrofit a significant amount of compute in the case of a deal. This would require an agency with a few thousand vetted installers and auditors, who would need to be trained to fit the package and ensure that data centers were in compliance.

Note that we aren’t discussing export controls here: this is because we are very uncertain if they are good or bad (opinions within AI Futures vary), and so they are discussed below.

Five low-confidence policies

A large class of interventions (e.g. export controls) involves improving the relative position of the US over China in adversarial cases (that is: they improve the BATNA). We think that these interventions have a strong case for them being good:

The US seems, overall, more likely to use the cosmic endowment wisely.

The US is currently ahead in the race to ASI. Increasing the US lead could allow it to spend a larger fraction of its resources on safety without relinquishing its lead.

However, there are also counterconsiderations. The default outcome of China losing the race (as happens in AI 2027) provides a strong incentive for China to push for a deal. If China is pushing for a deal, and the US doesn’t want to, then increasing the relative position of the US could make a deal much less likely.

This leaves us with significant sign-uncertainty – in worlds where the US would much prefer a deal and China is dragging its feet, improving the US’ ability to race may be useful to bring China to the table. In worlds where the two are closer in desire to reach a deal (e.g. they’re both fairly convinced that they do better in a world with a deal than without), derisking a race could shrink the bargaining range to the point where an agreement becomes less likely.

Some particular policies that others have advocated for, but we aren’t so sure about:

Building secure data centers (at SL5, resistant to state-level actors) would massively reduce the risk of weight theft, but might backfire by reducing visibility into AI progress (bad security is kind of like transparency), and therefore increase the likelihood of a secret intelligence explosion. Increasing security might also worsen race dynamics – if you think your models will be quickly stolen, you have less incentive to push the frontier.

Preparing to sabotage adversarial data centers (e.g. by ramping up offensive cyber) may increase the likelihood that the US gains a significant lead over China (and so could use this lead to push for a deal). However, this could hurt the likelihood of a deal, lead to hardening, which could be bad for the reasons given above, or even lead to preventive attacks from China that escalate into war.

GPU export controls are likely useful for Plan B worlds under short timelines – it would deny China access to significant amounts of compute – but incentivizes both chip smuggling, which makes Plan A harder to execute, and Chinese chip supply chain indigenization, which makes export controls later less effective. We are more excited about proposals along the lines of using export controls to incentivize the development of HEMs, by allowing exports of chips with appropriate verification mechanisms.

Semiconductor manufacturing equipment export controls are somewhat more promising, especially if paired with conditional relaxation of chip export controls for chips with location attestation and/or other hardware verification mechanisms. SME export controls delay China’s ability to indigenize, unlike controls on chips, but the overall effect of accelerating the Chinese SME industry may outweigh this in the long term.

A “Manhattan Project for AI” could be good for reducing domestic race dynamics, it could also very easily be bad for concentration of power reasons, or for normal incompetence reasons: the private sector is typically much more competent than governments. We are not optimistic about the ability of a US-only Manhattan project for AI to actually solve the alignment problem, especially if it isn’t designed and led by people who treat that problem as a priority.

Many thanks to Thomas Larsen, Joshua Turner, Daniel Kokotajlo and Miles Kodama for feedback on drafts of this post.

Looking forward to the deeper dive, but could you edit in some clear definitions for HEM and SME? I needed ChatGPT to guess that these mean Hardware-Enforcement Mechanism (or Monitoring) and Semiconductor Manufacturing Equipment.

Thank you so much for this excellent preliminary framework for thinking about AI governance in the US! Truly important stuff.

And the promise made in the italicized intro puts me in the mood of a child longing for Christmas:

“To any adversarial readers who want to dunk on our organizational policy recs, just wait a couple of months. We intend to publish a much more comprehensive ‘positive vision for AGI’, which will have much juicer targets to criticize.”