AI Futures Model: Dec 2025 Update

We've significantly improved our model of AI timelines and takeoff speeds!

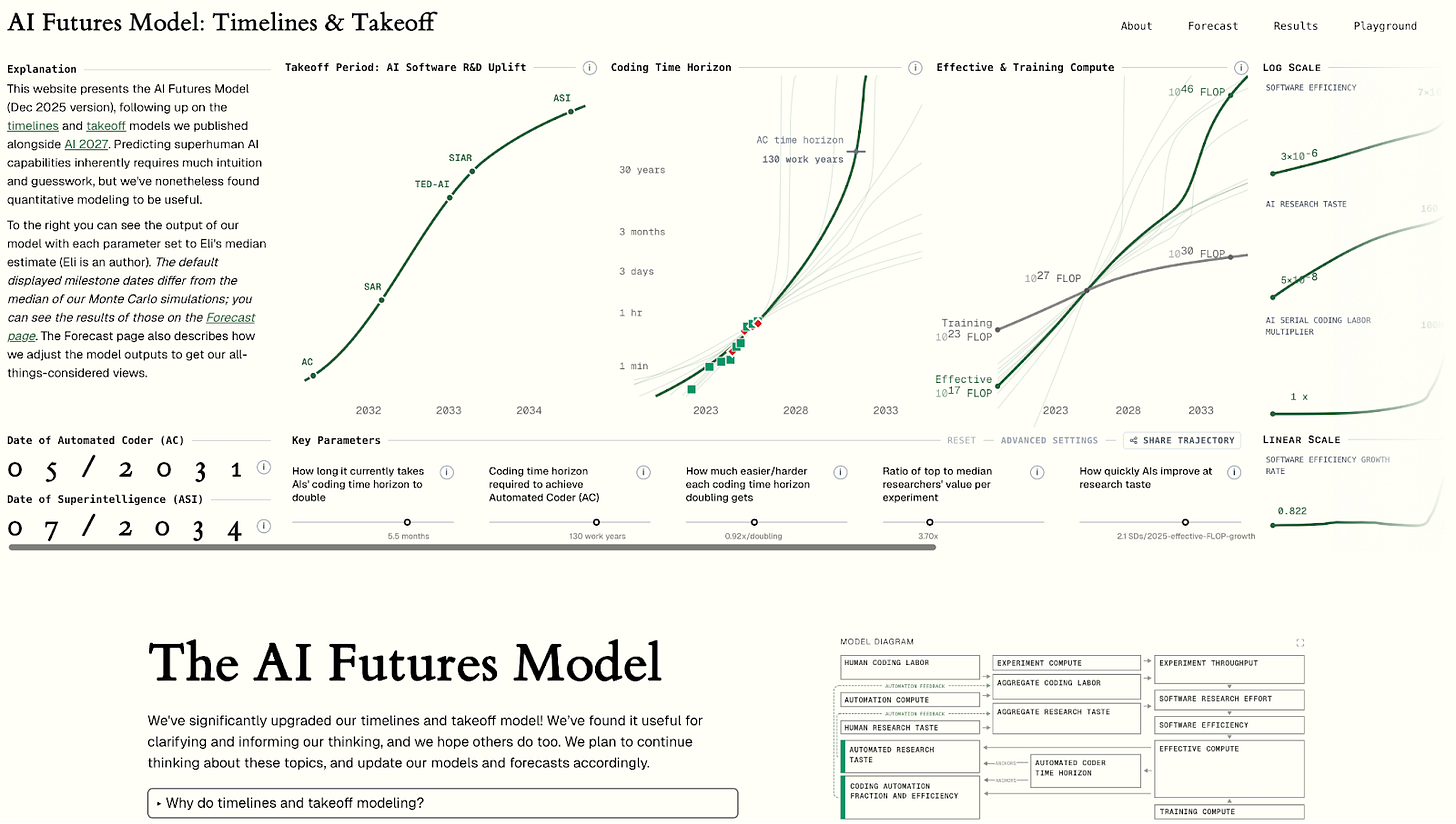

We’ve significantly upgraded our timelines and takeoff model! Our new unified model predicts when AIs will reach key capability milestones: for example, Automated Coder / AC (full automation of coding) and superintelligence / ASI (much better than the best humans at virtually all cognitive tasks). This post will briefly explain how the model works, present our timelines and takeoff forecasts, and compare it to our previous (AI 2027) models (spoiler: the AI Futures Model predicts longer timelines to full coding automation than our previous model by about 3-5 years, in significant part due to being less bullish on pre-full-automation AI R&D speedups). Added Jan 2026: see here for clarifications regarding how our forecasts have changed since AI 2027.

If you’re interested in playing with the model yourself, the best way to do so is via this interactive website: aifuturesmodel.com.

If you’d like to skip over the motivation for our model to an explanation for how it works, go here, The website has a more in-depth explanation of the model (starts here; use the diagram on the right as a table of contents), as well as our forecasts.

Why do timelines and takeoff modeling?

The future is very hard to predict. We don’t think this model, or any other model, should be trusted completely. The model takes into account what we think are the most important dynamics and factors, but it doesn’t take into account everything. Also, only some of the parameter values in the model are grounded in empirical data; the rest are intuitive guesses. If you disagree with our guesses, you can change them above.

Nevertheless, we think that modeling work is important. Our overall view is the result of weighing many considerations, factors, arguments, etc.; a model is a way to do this transparently and explicitly, as opposed to implicitly and all in our head. By reading about our model, you can come to understand why we have the views we do, what arguments and trends seem most important to us, etc.

The future is uncertain, but we shouldn’t just wait for it to arrive. If we try to predict what will happen, if we pay attention to the trends and extrapolate them, if we build models of the underlying dynamics, then we’ll have a better sense of what is likely, and we’ll be less unprepared for what happens. We’ll also be able to better incorporate future empirical data into our forecasts.

In fact, the improvements we’ve made to this model, as compared to our timelines model at the time we published AI 2027 (Apr 2025), have resulted in a roughly 3-5 year shift in our median for full coding automation. This has primarily come from improving our modeling of AI R&D automation. These modeling improvements have resulted in a larger change in our views than the new empirical evidence that we’ve observed. You can read more about the shift below.

Why our approach to modeling? Comparing to other approaches

AGI timelines forecasting methods

Trust the experts

Unfortunately, there is nothing close to an expert consensus, and it doesn’t seem like most experts have thought much about AGI1 forecasting (e.g. a 2023 survey observed huge framing effects depending on whether they asked for probabilities of milestones being achieved by certain years, or instead asked for years that correspond to percentiles). That 2023 survey of AI academics got an AGI median of 2047 or 2116, depending on the definition.2 There’s also this aggregation of Metaculus and Manifold markets which estimates 50% by 2030. As for the people building the technology, they tend to be more bullish; the most extreme among them (Anthropic and OpenAI) say things like 2027 and 2028. For a survey of older predictions and how they’ve fared, see this.

Given that experts disagree with each other and mostly seem to have not thought deeply about AGI forecasting, we think it’s important to work to form our own forecast.

Intuition informed by arguments

Can the current paradigm scale to AGI? Does it lack something important, like common sense, true original thinking, or online/continual learning (etc.)? Questions like these are very important and there are very many of them, far too many to canvas here. The way this method works is that everyone ingests the pile of arguments and considerations and makes up their own minds about which arguments are good and how they weigh against each other. This process inherently involves intuition/subjective-judgment, which is why we label it as “intuition.”

Which is not to denigrate it! We think that any AI forecaster worth their salt must engage in this kind of argumentation, and that generally speaking the more facts you know, the more arguments you’ve considered and evaluated, the more accurate your intuitions/vibes/judgments will become. Also, relatedly, your judgment about which models to use, and how much to trust them, will get better too. Our own all-things-considered views are only partially based on the modelling we’ve done; they are also informed by intuitions.

But we think that there are large benefits to incorporating quantitative models into our forecasts: it’s hard to aggregate so many considerations into an overall view without using a quantitative framework. We’ve also found that quantitative models help prioritize which arguments are most important to pay attention to. And our best guess is that overall, forecasts by quantitative trend extrapolation have a better historical track record than intuitions alone.

Revenue extrapolation

Simple idea: extrapolate AI revenue until it’s the majority of world GDP. Of course, there’s something silly about this; every previous fast-growing tech sector has eventually plateaued… That said, AI seems like it could be the exception, because in principle AI can do everything. Now that AI is a major industry, we think this method provides nonzero evidence. According to this Epoch dataset, frontier AI company revenue is something like $20B now and growing around 4.1x/yr. This simple extrapolation gets to $100T annualized revenue around the end of 2031.3

We give weight to revenue extrapolation in our all-things-considered views, but on the other hand revenue trends change all the time and we’d like to predict the underlying drivers of how it might change. Also, it’s unclear what revenue threshold counts as AGI. Therefore, we want to specifically extrapolate AI capabilities.

Compute extrapolation anchored by the brain

The basic idea is to estimate how much compute it would take to get AGI, anchored by the human brain. Then predict that AGI will happen when we have that much compute. This approach has gone through a few iterations:

Hans Moravec, Ray Kurzweil, and Shane Legg pioneered this method, predicting based on the amount of operations per second that the human brain does. Moravec predicted AGI in 2010 in 1988, then revised it to 2040 in 1999. Kurzweil and Legg each predicted AGI in the late 2020s in about 2000.4

Ajeya Cotra’s 2020 biological anchors report instead predicted AGI5 based on how much compute it would take to train the human brain. Cotra also estimated how much algorithmic progress would be made, converting it into the equivalent of training compute increases to get “effective compute”. The report predicted a median of 2050.

Davidson’s Full Takeoff Model and Epoch’s GATE used the same method as bio anchors to determine the AGI training compute requirement, but they also modeled how AI R&D automation would shorten timelines. They modeled automation by splitting up AI software and hardware R&D into many tasks, then forecasting the effective compute gap between 20% task automation and 100% automation. The percentage of tasks automated, along with experiment compute and automation compute, determine the magnitude of inputs to AI R&D. These inputs are converted to progress in software efficiency using a semi-endogeneous growth model. Software efficiency is then multiplied by training compute to get effective compute.

At the time the FTM was created it predicted AGI in 2040, with the parameter settings chosen by Davidson. But both compute and algorithmic progress has been faster than they expected. When the FTM is updated to take into account this new data, it gives shorter medians in the late 2020s or early 2030s. Meanwhile, with GATE’s median parameters, it predicts AGI in 2034.

Overall, this forecasting method seems to us to have a surprisingly good track record: Moravec, Kurzweil, and Legg especially look to have made predictions a long time ago that seem to hold up well relative to what their contemporaries probably would have said. And our model follows these models by modeling training compute scaling, though in most of our simulations the majority of progress toward AGI comes from software.

Capability benchmark trend extrapolation

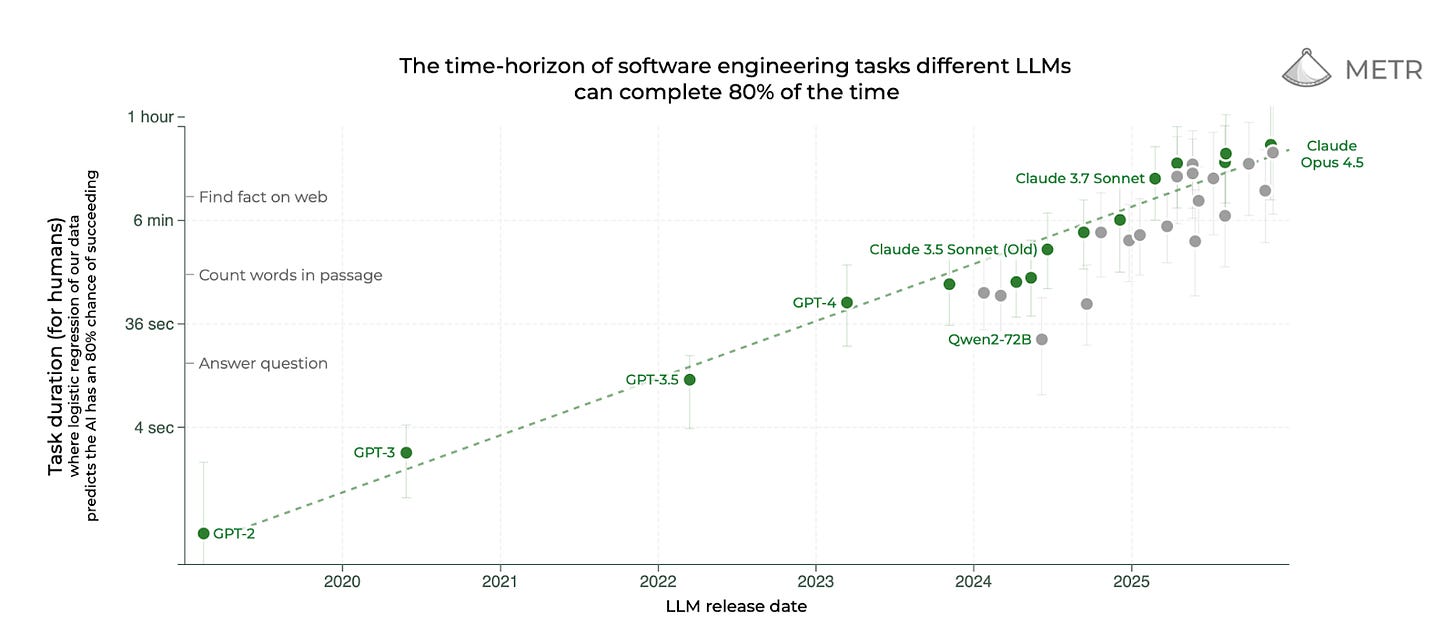

This is our approach! We feel that now, in 2025, we have better evidence regarding the AGI effective compute requirement than comparisons to the human brain: specifically, we can extrapolate AIs’ performance on benchmarks. This is how the timelines portion of our model works. We set the effective compute required for AGI by extrapolating METR’s coding time horizon suite, METR-HRS.

We think it’s pretty great. Benchmark trends sometimes break, and benchmarks are only a proxy for real-world abilities, but… METR-HRS is the best benchmark currently available for extrapolating to very capable AIs, in our opinion. We think it’s reasonable to extrapolate that straight line into the future for at least the next few years.6

METR itself did a simple version of this extrapolation which assumed exponential growth in time horizons in calendar time. But this doesn’t account for AI R&D automation, changes to human labor or compute growth, or the possibility of time horizon doublings getting easier or harder at higher horizons.7

Our previous timelines model took all of these into account, though more crudely than our new AI Futures Model. Our previous model with median parameters predicted superhuman coder (SC) medians of 2027 to 2028, while our new model predicts 2032. The difference mostly comes from improvements to how we’re modeling AI R&D automation. See below for details.

Post-AGI takeoff forecasts

The literature on forecasting how capabilities progress after full automation of AI R&D is even more nascent than that which predicts AGI timelines. Past work has mostly fallen into one of two buckets:

Qualitative arguments or oversimplified calculations sketching why takeoff might be fast or slow: for example, Intelligence Explosion Microeconomics by Eliezer Yudkowsky (arguing for fast takeoff) or Takeoff speeds by Paul Christiano (arguing for slow takeoff).8

Models of the software intelligence explosion (SIE), i.e. AIs getting faster at improving its own capabilities without additional compute: in particular, How quick and big would a software intelligence explosion be? by Davidson and Houlden.9

As in timelines forecasting, we think that qualitative arguments are valuable but we think that modeling is a useful complement to qualitative arguments.

Davidson and Houlden focuses primarily on trends of how much more efficiently AIs have been able to achieve the same performance when determining whether there will be an SIE.10 Meanwhile, we focus on estimates of the quality of AIs’ research taste, i.e. how good the AI is at choosing research directions, selecting and interpreting experiments, etc. We think that focusing on research taste quality is a more useful lens from which to view a potential SIE. If there’s an SIE we expect that it will primarily be driven by improvements in research taste.

Furthermore, because our takeoff model is integrated into a more expansive quantitative model, we have other advantages relative to Davidson and Houlden. For example, we can account for increases in the AGI project’s compute supply.11

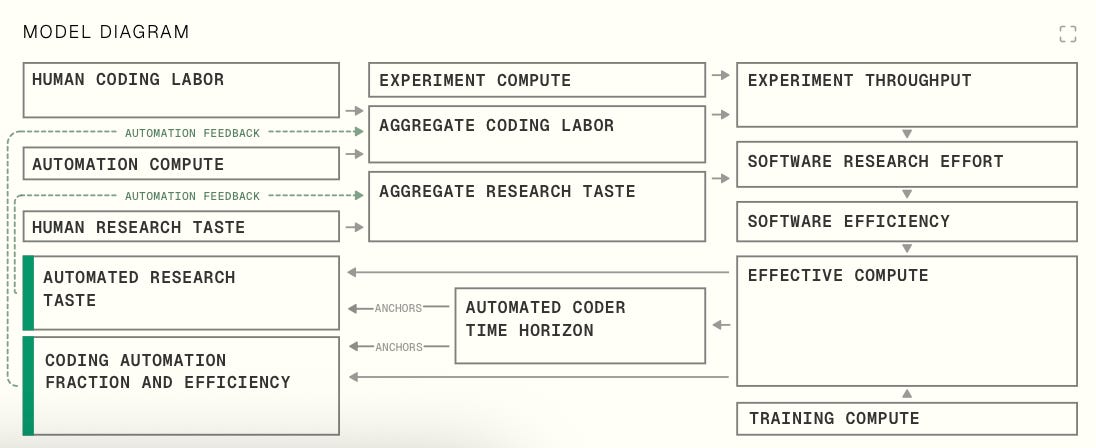

How our model works

On the web app, there’s an interactive diagram explaining the parts of the model and how they relate to each other, with a corresponding full model explanation:

Here we’ll just give a brief overview.

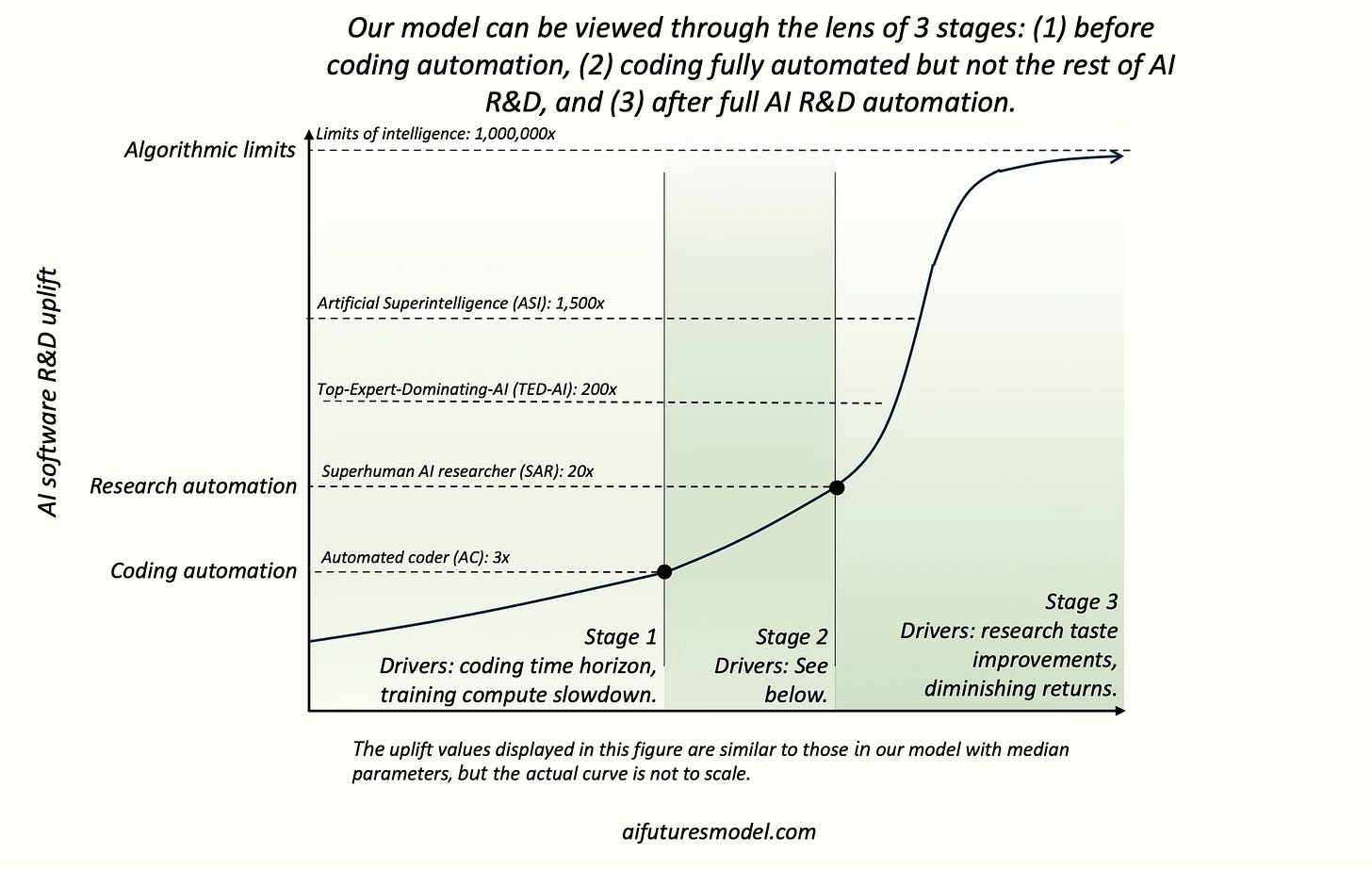

Our model’s primary output is the trajectory of AIs’ abilities to automate and accelerate AI software R&D. We also include milestones tracking general capabilities, but these are calculated very roughly.

Our model can intuitively be divided into 3 stages. Although the same formulas are used in Stages 1, 2, and 3, new dynamics emerge at certain milestones (Automated Coder, Superhuman AI Researcher), and so these milestones delineate natural stages.

Stage 1: Automating coding

First we’ll discuss how our model predicts when coding will be fully automated. Stage 1 predicts when an Automated Coder (AC) arrives.

Automated Coder (AC). An AC can fully automate an AGI project’s coding work, replacing the project’s entire coding staff.12

Our starting point is to take the METR graph and extrapolate it exponentially, as METR does, then make a guess about what agentic coding time horizon would correspond to the AC milestone. This gives us an estimated date for when AC will be achieved.

However, this simple extrapolation misses out on many important factors, such as:

The inputs to AI progress — most notably compute, but also labor, data, etc. — won’t keep growing at the same rates forever. There’s a significant chance that growth rates will slow in the near future e.g. as we run up against limits of chip production, investment, recruiting pipelines, energy, etc. This could cause the trend to bend downwards.

Automation of AI R&D. Already many AI researchers claim that AI is accelerating their work.13 The extent to which it is actually accelerating their work is unfortunately unclear, but probably there is a nonzero effect already and probably this acceleration effect will increase as AIs become more capable. This could cause the trend to bend upwards.

Superexponential time horizon growth (independent from AI R&D automation). Eventually there will be AI systems which outperform humans at all horizon lengths; therefore, the trend should eventually shoot to infinity.14 Therefore, we think we should use a superexponential trend rather than an exponential trend. (This is confusing and depends on how you interpret horizon lengths, see here for more discussion. If you disagree with this, our model allows you to use an exponential trend if you like, or even subexponential.)

Our model up through AC still centrally involves the METR trend, but it attempts to incorporate the above factors and more.15 It also enables us to better represent/incorporate uncertainty, since we can do Monte Carlo simulations with different parameter settings.

Stage 2: Automating research taste

Besides coding, we track one other type of skill that is needed to automate AI software R&D: research taste. While automating coding makes an AI project faster at implementing experiments, automating research taste makes the project better at setting research directions, selecting experiments, and learning from experiments.

Stage 2 predicts how quickly we will go from an automated coder (AC) to a Superhuman AI researcher (SAR), an AI with research taste matching the top human researcher.

Superhuman AI Researcher (SAR): A SAR can fully automate AI R&D, making all human researchers obsolete.16

The main drivers of how quickly Stage 2 goes is:

How much automating coding speeds up AI R&D. This depends on a few factors, for example how severely the project gets bottlenecked on experiment compute.

How good AIs’ research taste is at the time AC is created. If AIs are better at research taste relative to coding, Stage 2 goes more quickly.

How quickly AIs get better at research taste. For a given amount of inputs to AI progress, how much more value does one get per experiment?

Stage 3: The intelligence explosion

Finally, we model how quickly AIs are able to self-improve once AI R&D is fully automated and humans are obsolete. The endpoint of Stage 3 is asymptoting at the limits of intelligence.

The primary milestones we track in Stage 3 are:

Superintelligent AI Researcher (SIAR). The gap between a SIAR and the top AGI project human researcher is 2x greater than the gap between the top AGI project human researcher and the median researcher.17

Top-human-Expert-Dominating AI (TED-AI). A TED-AI is at least as good as top human experts at virtually all cognitive tasks. (Note that the translation in our model from AI R&D capabilities to general capabilities is very rough.)18

Artificial Superintelligence (ASI). The gap between an ASI and the best humans is 2x greater than the gap between the best humans and the median professional, at virtually all cognitive tasks.19

In our simulations, we see a wide variety of outcomes ranging from a months-long takeoff from SAR to ASI, to a fizzling out of the intelligence explosion requiring further increases in compute to get to ASI.

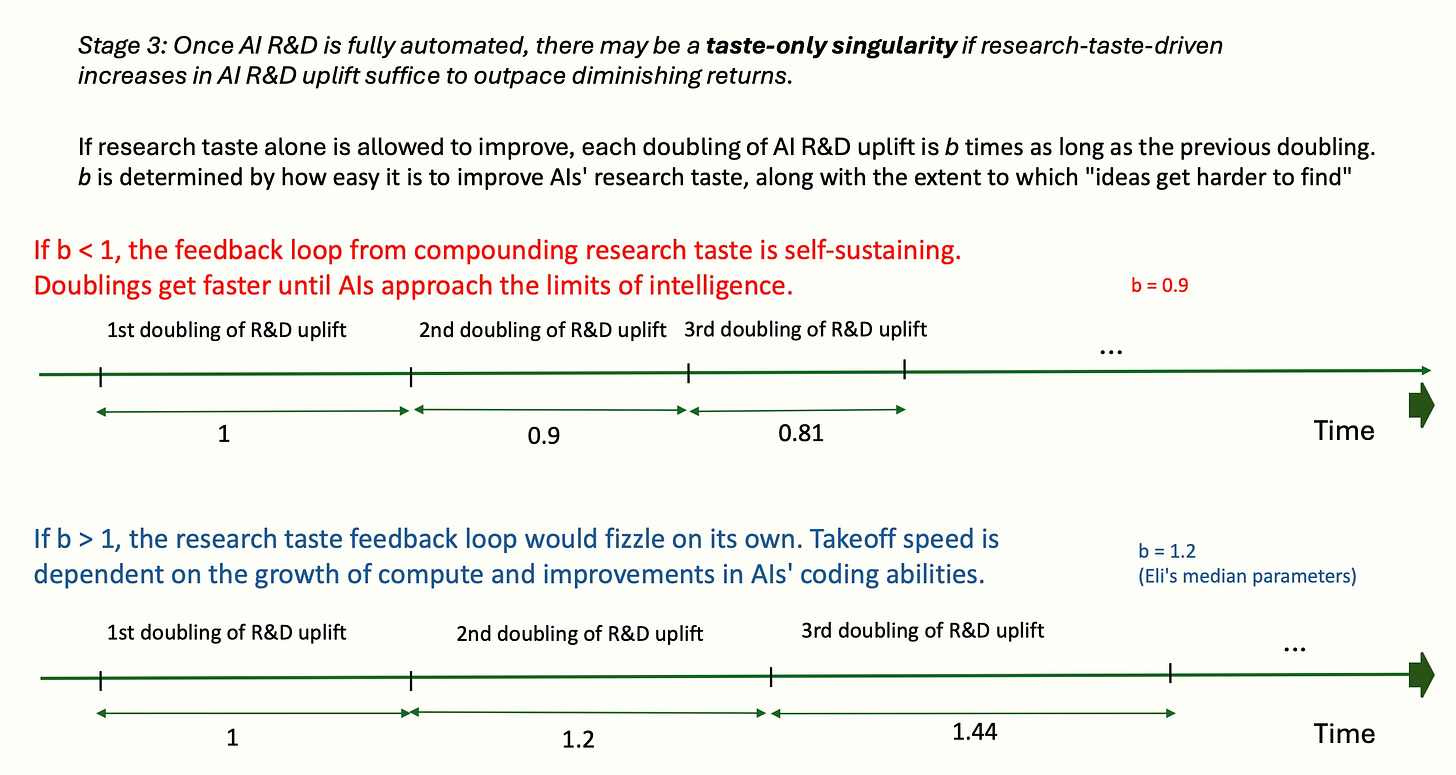

To achieve a fast takeoff, there usually needs to be a feedback loop such that each successive doubling of AI capabilities takes less time than the last. In the fastest takeoffs, this is usually possible via a taste-only singularity, i.e. the doublings would get faster solely from improvements in research taste (and not increases in compute or improvements in coding). Whether a taste-only singularity occurs depends on which of the following dominates:

The rate at which (experiment) ideas become harder to find. Specifically, how much new “research effort” is needed to achieve a given increase in AI capabilities.

How quickly AIs’ research taste improves. For a given amount of inputs to AI progress, how much more value does one get per experiment?

Continued improvements in coding automation matter less and less, as the project gets bottlenecked by their limited supply of experiment compute.

Timelines and takeoff forecasts

The best place to view our results is at https://www.aifuturesmodel.com/forecast.

In this section we will discuss both our model’s outputs and our all-things-considered views. As previously mentioned, we are uncertain, and don’t blindly trust our models. Instead we look at the results of the model but then ultimately make adjustments based on intuition and other factors. Below we describe the adjustments that we make on top of this model, and the results.

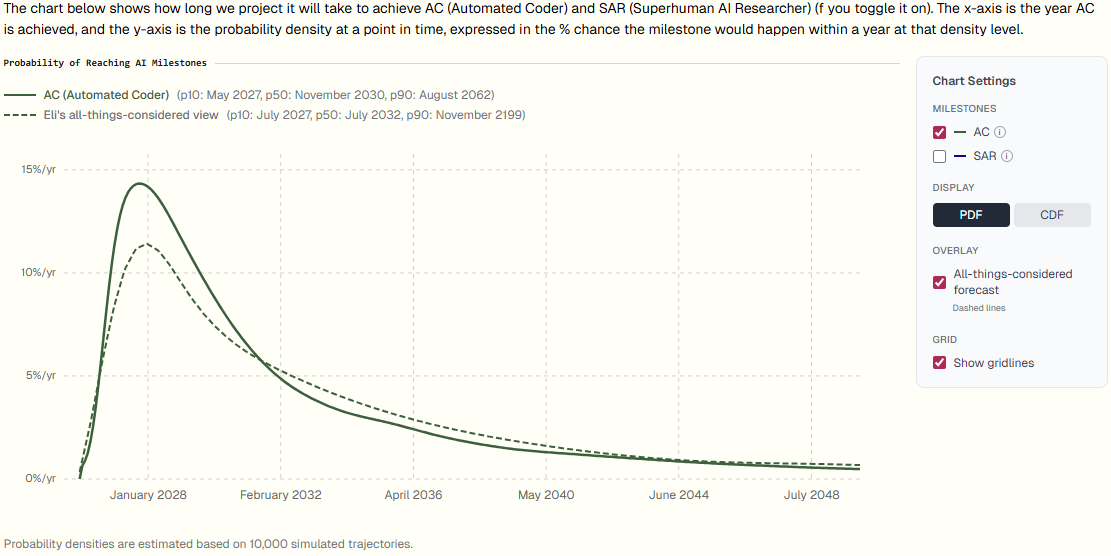

Eli

Here is the model’s output with my parameters along with my all-things-considered views.

To adjust for factors outside of the model, I’ve: lengthened timelines (median from late 2030 to mid 2032), driven primarily by unknown model limitations and mistakes and the potential for data bottlenecks that we aren’t modeling. In summary:

Unknown model limitations and mistakes. With our previous (AI 2027) timelines model, my instinct was to push my overall forecasts longer due to unknown unknowns, and I’m glad I did. My median for SC was 2030 as opposed to the model’s output of Dec 2028, and I now think that the former looks more right. I again want to lengthen my overall forecasts for this reason, but less so because our new model is much more well-tested and well-considered than our previous one, and is thus less likely to have simple bugs or unknown simple conceptual issues.

Data bottlenecks. Our model implicitly assumes now that any data progress is proportional to algorithmic progress. But data in practice could be either more or less bottlenecking. My guess is that modeling data would lengthen timelines a bit, at least in cases where synthetic data is tough to fully rely upon.

I will also increase the 90th percentile from 2062. My all-things-considered distribution is: 10th percentile 2027.5, 50th percentile 2032.5, 90th percentile 2085. You can see all of the adjustments that I considered in this supplement.

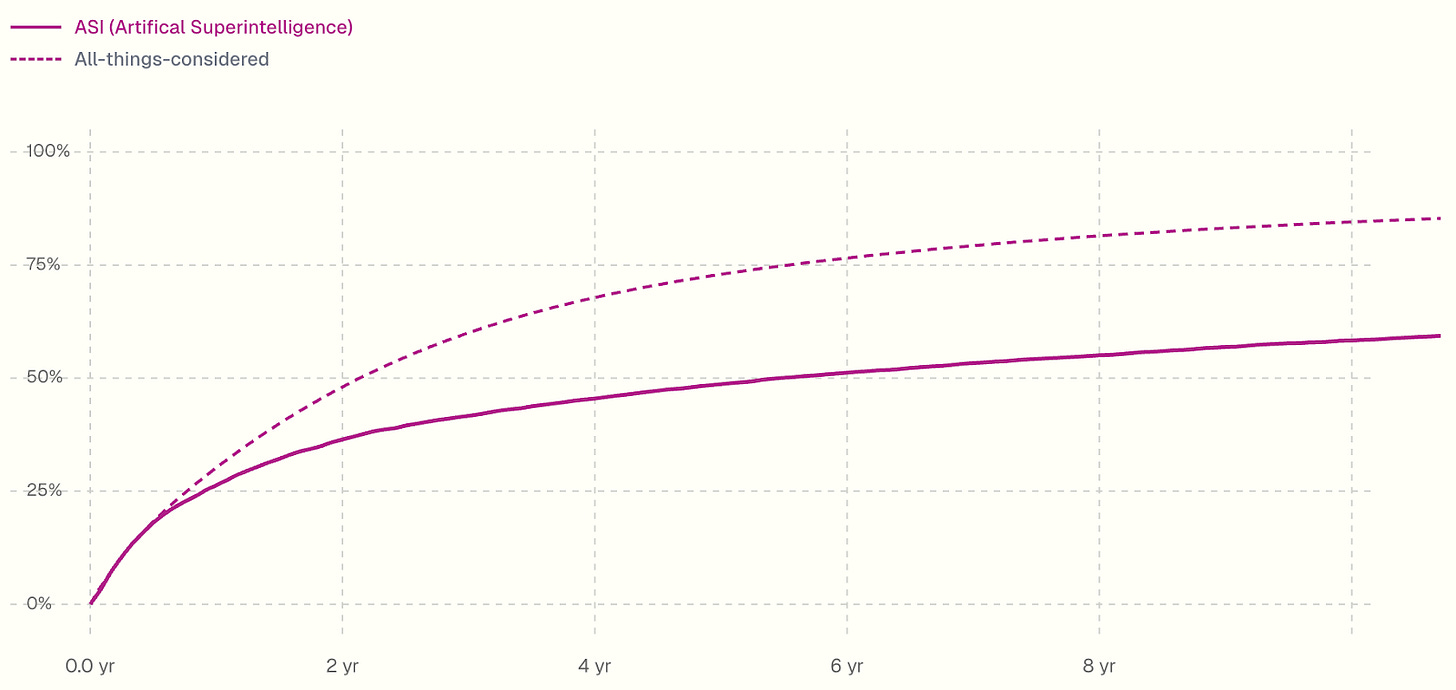

Now I’ll move on to takeoff.

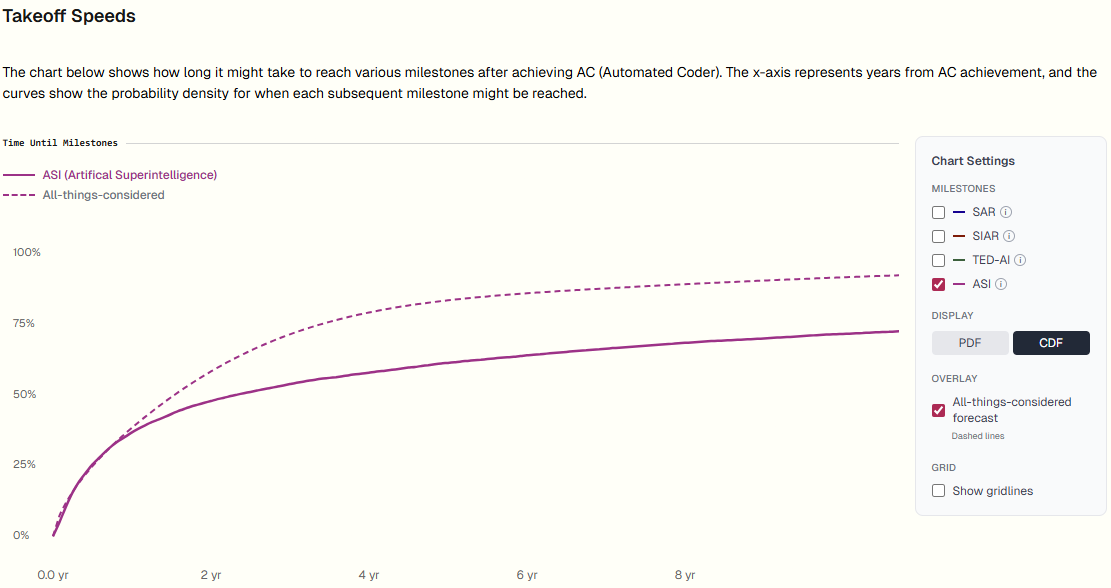

To get my all-things-considered views I: increase the chance of fast takeoff a little (I change AC to ASI in <1 year from 26% to 30%), and further increase the chance of <3 year takeoffs (I change the chance of AC to ASI in <3 years from 43% to 60%).

The biggest reasons I make my AI-R&D-specific takeoff a bit faster are:

Automation of hardware R&D, hardware production, and general economic automation. We aren’t modeling these, and while they have longer lead times than software R&D, a year might be enough for them to make a substantial difference.

Shifting to research directions which are less compute bottlenecked might speed up takeoff, and isn’t modeled. Once AI projects have vast amounts of labor, they can focus on research which loads more heavily on labor relative to experiment compute than current research.

(1) leads me to make a sizable adjustment to the tail of my distribution. I think modeling hardware and economic automation would make it more likely that if there isn’t a taste-only singularity, we still get to ASI within 3 years.

I think that, as with timelines, for takeoff unknown limitations and mistakes in expectation point towards things going slower. But unlike with timelines, there are counter-considerations that I think are stronger. You can see all of the adjustments that I considered in this supplement.

Daniel

First, let me say a quick prayer to the spirit of rationality, who infrequently visits us all:

On the subject of timelines, I don’t immediately know whether my all-things-considered view should be more or less bullish than the model. Here are a few considerations that seem worth mentioning to me:

First of all, this model is in-the-weeds / gearsy. (Some people might call it “inside-viewy” but I dislike that term.) I think it’s only appropriate to use models like this if you’ve already thought through more straightforward/simple considerations like “Is the phenomena in question [AGI] even possible at all? Do serious experts take it seriously? Are there any obvious & solid arguments for why this is a nothingburger?” I have thought through those kinds of things, and concluded that yes, AGI arriving in the next decade seems a very serious possibility indeed, worthy of more gearsy investigation. If you disagree or are curious what sorts of considerations I’m talking about, a partial list can be found in this supplement.

I think this model is the best model of AI R&D automation / intelligence explosion that currently exists, but this is a very poorly understood phenomenon and there’s been very little attention given to it, so I trust this model less when it comes to takeoff speeds than I do when it comes to timelines. (And I don’t trust it that much when it comes to timelines either! It’s just that there isn’t any single other method I trust more…)

I notice a clash between what the model says and my more intuitive sense of where things are headed. I think probably it is my intuitions that are wrong though, which is why I’ve updated towards longer timelines; I’m mostly just going with what the model says rather than my intuitions. However, I still put some weight on my intuitive sense that, gosh darn it, we just aren’t more than 5 years away from the AC milestone – think about how much progress has happened over the last 5 years! Think about how much progress in agentic coding specifically has happened over the last year! Over the past decade I’ve learned to trust my intuitive sense of where things are headed a decent amount, because it’s worked pretty well over the years (e.g. What 2026 Looks Like was basically entirely intuition-based)

More detail on vibes/intuitions/arguments:

I’ve been very unimpressed by the discourse around limitations of the current paradigm. The last ten years have basically been one vaunted limitation after another being overcome; Deep Learning has hit a wall only in the sense that Godzilla has hit (and smashed through) many walls.

However, two limitations do seem especially plausible to me: Online/continual learning and data efficiency. I think there has been some progress in both directions over the past years, but I’m unclear on how much, and I wouldn’t be that surprised if it’s only a small fraction of the distance to human level.

That said, I also think it’s plausible that human level online/continual learning is only a few years away, and likewise for data-efficiency. I just don’t know. (One data point: claim from Anthropic researcher)

Meanwhile, I’m not sure either of those things are necessary for AI R&D to accelerate dramatically due to automation. People at Anthropic and OpenAI already report that things are starting to speed up due to AI labor, and I think it’s quite plausible that massively scaled-up versions of current AI systems (trained on OOMs more diverse RL environments, including many with OOMs longer horizon lengths) could automate all or almost all of the AI R&D process. The ability to learn from the whole fleet of deployed agents might compensate for the data-inefficiency, and the ability to manage huge context window file systems, update model weights regularly, and quickly build and train on new RL environments might compensate for lack of continual learning.

And once AI accelerates dramatically due to automation, paradigm shifts of the sort mentioned above will start to happen soon after.

Summing up: Qualitatively, my intuitive sense of what’s going to happen in the next few years is, well, basically the same sequence of events described in AI 2027, just maybe taking a year or two longer to play out, and with various other minor differences (e.g. I don’t expect any one company to have as much of a lead as OpenBrain does in the scenario).

I’m also quite nervous about relying so much on the METR horizon trend. I think it’s the best single source of evidence we have, but unfortunately it’s still pretty limited as a source of evidence.

It is uncertain how it’ll extrapolate into the future (exponential or superexponential? If superexponential, how superexponential? Or should we model new paradigms as a % chance per year of changing the slope? What even is the slope right now, it seems to maybe be accelerating recently?)

…and also uncertain how to interpret the results (is a 1 month 80% horizon enough? Or do we need 100 years?).

There are also some imperfections in the methodology which complicate things. E.g. if I understand correctly the human baseliners for the various tasks were not of the same average skill level, but instead the longer-horizon tasks tended to have higher-skill human baseliners. Also, the sigmoid fit process is awkwardly non-monotonic, meaning there are some cases in which a model getting strictly better (/worse) at some bucket of tasks can decrease (/increase) its METR-reported horizon length! My guess is that these issues don’t make a huge difference in practice, but still. I hope that a year from now, it becomes standard practice for many benchmark providers to provide information about how long it took human baseliners to complete the tasks, and the ‘skill level’ of the baseliners. Then we’d have a lot more data to work with.

Also, unfortunately, METR won’t be able to keep measuring their trend forever. It gets exponentially more expensive for them to build tasks and collect human baselines as the tasks get exponentially longer. I’m worried that by 2027, METR will have basically given up on measuring horizon lengths, which is scary because then we might not be able to tell whether horizon lengths are shooting up towards infinity or continuing to grow at a steady exponential pace.

I think a much better trend to extrapolate, if only we had the data, would be coding uplift. If we had e.g. every 6 months for the past few years a high-quality coding uplift study, we could then extrapolate that trend into the future to predict when e.g. every engineer would be a 10x engineer due to AI assistance. (Then we’d still need to predict when research taste would start to be noticeably uplifted by AI / when AIs would surpass humans in research taste; however, I think it’s a reasonable guess right now that when coding is being sped up 10x, 100x, etc. due to highly autonomous AI coding agents, research taste should be starting to improve significantly as well.20 At least I feel somewhat better about this guess than I do about picking any particular threshold of METR horizon length and guessing that it corresponds to a particular level of experiment selection skill, which is what we currently do.)

Relatedly, I’m also interested in the simple method of extrapolating AI revenue growth trends until AI revenue is most of the world economy. That seems like a decent proxy for when AGI will be achieved. I trust this method less than our model for obvious reasons, but I still put some weight on it. What does it say? Well, it says “Early 2030s.” OK.

I’m also interested in what our model says with a pure exponential trend extrapolation for METR instead of the superexponential (I prefer the superexponential on theoretical grounds, though note also that there seems to be a recent speeding up of the METR trend and a corresponding speedup in the trend on other benchmarks). Pure exponential trend, keeping my other parameters fixed, gets to AC 5 years later, in 2034. That said, if we use the more recent ~4 month doubling time that seems to characterize the RL era, even an exponential trend gets to AC in 2030, keeping other parameters fixed. I’m not sure I should keep my other parameters fixed though, particularly the AC coding time horizon requirement seems kinda up in the air since the change to exponential slope corresponds to a change in how I interpret horizon lengths in general.21

One factor weighing on my mind is the apparent recent speedup in AI capabilities progress–e.g. the slope of the METR trend seems notably higher since 2024 than it was before. This could be taken as evidence in favor of a (more) superexponential trend overall…

However, I’m currently leaning against that interpretation, for two reasons. First, the speedup in the trend isn’t just for the METR trend, it’s also for other benchmarks, which are not supposed to be superexponential. Secondly, there’s another very plausible explanation for what’s going on, which is that starting in 2024 the companies started scaling up RL a lot. But they won’t be able to keep scaling it at the same pace, because they’ll run into headwinds as RL becomes the majority of training compute. So on this view we should expect the rate of growth to revert towards the long-run average starting about now (or however long it takes for RL compute to become the majority of total training compute).

That said, I still think it’s plausible (though not likely) that actually what we are seeing is the ominous uptick in the rate of horizon length growth that is predicted by theory to happen a year or two before horizon lengths shoot to infinity.

Also, like Eli said above, I feel that I should err on the side of caution and that for me that means pushing towards somewhat longer timelines.

Finally, I have some private info which pushes me towards somewhat shorter timelines in expectation. My plan is to circle back in a month or three when more info is available and update my views then, and I currently expect this update to be towards somewhat shorter timelines though it’s unclear how much.

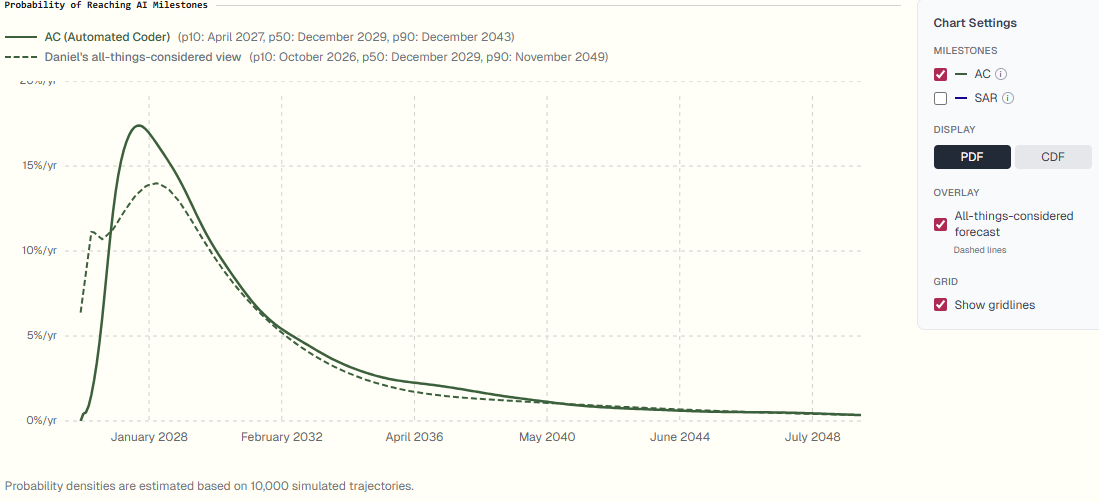

Weighing all these considerations, I think that my all-things-considered view on timelines will be to keep the median the same, but increase the uncertainty in both directions, so that there’s a somewhat greater chance of things going crazy in the next year (say, 9% by EOY 2026) and also a somewhat greater chance of things taking decades longer (say, still 6% that there’s no AGI even in 2050).

So, here’s my all-things-considered distribution as of today, Dec 30 2025:

On takeoff speeds:

I think my thoughts on this are pretty similar to Eli’s, modulo differences implied by our different parameter settings. Basically, take what the model (with my parameters) says, and then shift some probability mass away from the slower end and put it on the faster end of the range.

Also, whereas our model says that takeoff speeds are correlated with timelines such that shorter timelines also tends to mean faster takeoff, I’m not sure that’s correct and want to think about it more. There’s a part of me that thinks that on longer timelines, takeoff should be extremely fast due to the vast amounts of compute that will have piled up by then and due to the compute-inefficiency of whatever methods first cross the relevant thresholds by then.

So here’s a quick distribution I just eyeballed:

What info I’ll be looking for in the future & how I’ll probably update:

Obviously, if benchmark trends (especially horizon length) keep going at the current pace or accelerate, that’ll be an update towards shorter timelines. Right now I still think it’s more likely than not that there’ll be a slowdown in the next year or two.

I’m eager to get more information about coding uplift. When we have a reliable trend of coding uplift to extrapolate, I’ll at the very least want to redo my estimates of the model parameters to fit that coding uplift trend, and possibly I’d want to rethink the model more generally to center on coding uplift instead of on horizon length.

If AI revenue growth stays strong (e.g. 4xing or more in 2026) that’s evidence for shorter timelines vs. if it only grows 2x or less that’s evidence for longer timelines.

I’m eager to get more information about the ‘slope’ of the performance-as-a-function-of-time graph for various AI models, to see if it’s been improving over time and how far away it is from human performance. (See this discussion) This could potentially be a big update for me in either direction.

As for takeoff speeds, I’m mostly interested in thinking more carefully about that part of our model and seeing what improvements can be made.22 I don’t think there’ll be much empirical evidence one way or another in the next year. Or rather, I think that disputes about the proper way to model takeoff matter more than evidence about the value of various parameters, at this stage. That said, I’ll be keen to get better estimates of some of the key parameters too.

Of course I’m also interested to hear the feedback/criticism/etc. from others about the model and the parameters and the overall all things considered view. I wouldn’t be surprised if I end up changing my mind significantly on the basis of arguments I haven’t thought of yet.

…this list is nowhere near exhaustive but that’s enough for now I guess.

Comparison to our previous (AI 2027) timelines and takeoff models

These section focus specifically on the model results with Eli’s parameter estimates (for both the AI Futures Model and the AI 2027 model).

Added Jan 2026: see here for clarifications regarding how our forecasts have changed since AI 2027.

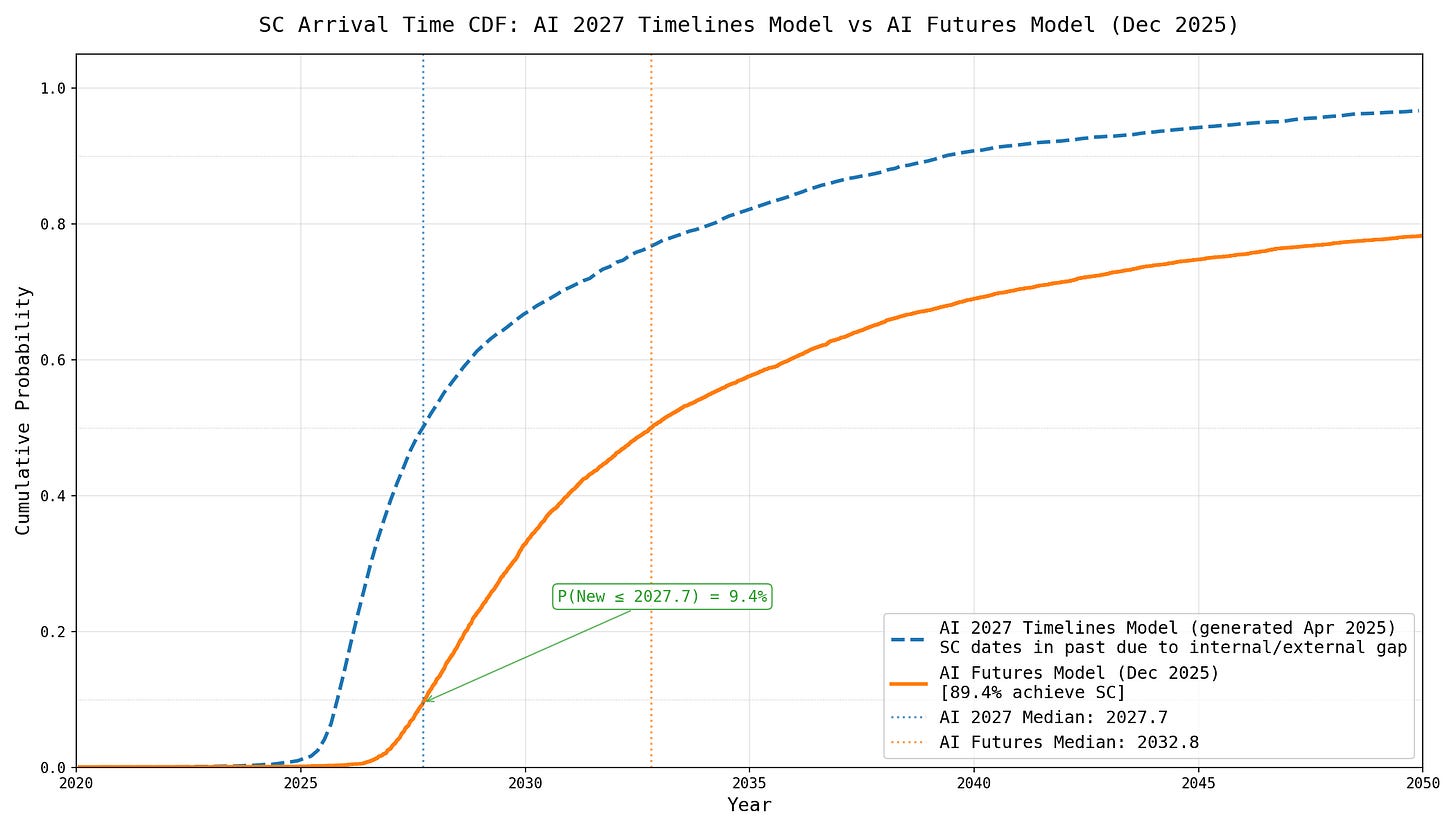

Timelines to Superhuman Coder (SC)

This section focuses on timelines to superhuman coder (SC), which was our headline milestone in our AI 2027 timelines model: an SC represents an AI that autonomously is as productive as an AGI project modified to have all coders as competent as their best, speeding them each up by 30x, and getting 30 copies of each of them.23

We’ll discuss only the AI 2027 time horizon extension model in this section, due to it being simpler than the benchmarks and gaps version.24 Below we compare the forecasted distribution of the AI 2027 model against that of the AI Futures Model.

Edited Jan 8: updated the above figure and below description to fix an issue, moving the new model’s SC timelines back slightly.

We see that the AI Futures Model median is 5 years later than the AI 2027 model, and that it assigns a 9% chance that SC happens before the time horizon extension’s median. From now onward, we will focus on the trajectory with median parameters rather than distributions of SC dates, for ease of reasoning.

The AI 2027 time horizon extension model, with parameters set to their median values, predicts SC in Jan 2027 given superexponential-in-effective-compute time horizon growth, and SC in Sep 2028 given exponential time horizon growth. Meanwhile, the new model with median parameters predicts SC in Dec 2031. This is a 3.25-5 year difference! From now on we’ll focus on the 5 year difference, i.e. consider superexponential growth in the time horizon extension model. This is a closer comparison because in our new model, our median parameter estimate predicts superexponential-in-effective-compute time horizon growth.

The biggest reason for this difference is that we model pre-SC AI R&D automation differently, which results in such automation having a much smaller effect in our new model than in the AI 2027 one. The 5 year increase in median comes from:

Various parameter estimate updates: ~1 year slower. These are mostly changes to our estimates of parameters governing the time horizon progression. Note that 0.6 years of this is from the 80% time horizon progression being slower than our previous median parameters predicted, but since we are only looking at 80% time horizons we aren’t taking into account the evidence that Opus 4.5 did well on 50% time horizon.

Less effect from AI R&D automation pre-SC: ~2 years slower. This is due to:

Taking into account diminishing returns: The AI 2027 timelines model wasn’t appropriately taking into account diminishing returns to software research. It implicitly assumes that exponential growth in software efficiency is not getting “harder” to achieve, such that if AIs gave a software R&D uplift of 2x in perpetuity, the software efficiency growth rate would speed up by 2x in perpetuity. We didn’t realize this implicit assumption and have now fixed it.

Less AI software R&D uplift from pre-SC AIs: The interpolation method used to get AI software R&D uplift values in the AI 2027 model in between present day and SC gave much higher intermediate values than the uplift we end up with in our new model. We previously modeled 50% of the way to SC in effective compute OOMs as resulting in 50% of the way to SC in terms of log(uplift), but our new model is more pessimistic. Partially, this is because the AI 2027 model had a bug in how AI software R&D was interpolated between present AIs and SC. But that only accounts for half of the difference, the other half comes from us choosing an interpolation method that was more optimistic about pre-SC speedups than the AI Futures Model.

Compute and labor input time series adjustments: ~1 year slower. That is, we now project slower growth in the leading AI project’s compute amounts and in their human labor force. Read about the AI Futures Model’s input time series here.

Modeling experiment compute: ~1 year slower. Previously we were only modeling labor as an input to software progress, not experiment compute.

You can read more about these changes and their effects in our supplementary materials.

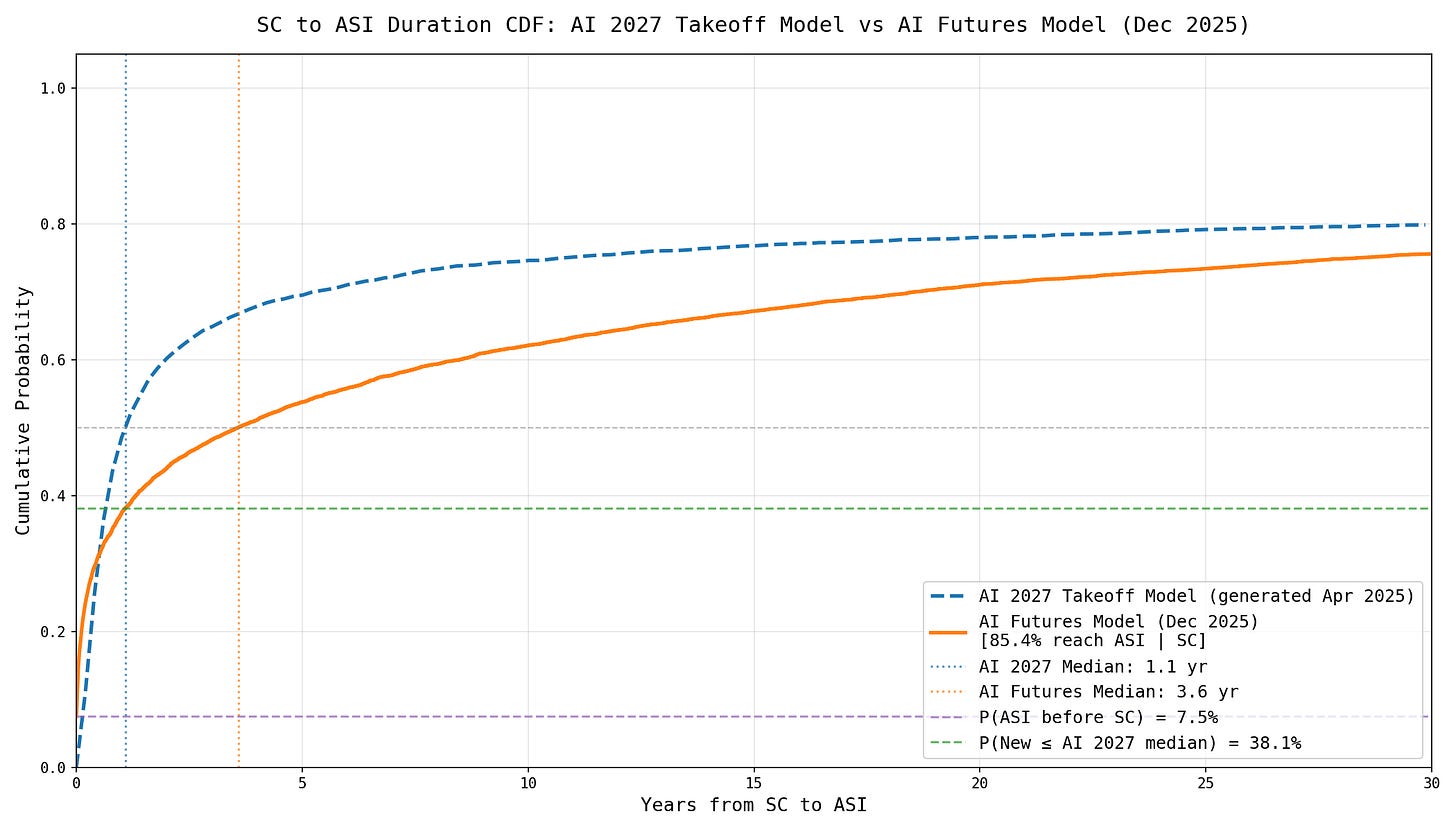

Takeoff from Superhuman Coder onward

The AI Futures Model predicts a slower median takeoff than our AI 2027 takeoff model. Below we graph each of their forecasted distributions for how long it will take to go from SC to ASI.

Edited Jan 8: updated the above figure and below description to fix an issue, moving the new model’s takeoff to be a bit slower.

We see that while the AI Futures Model’s median is longer than the AI 2027 one, it still puts 38% probability of takeoff as fast as AI 2027’s median. On the other hand, the AI Futures Model’s cumulative probability gets closer to the AI 2027 model as the AC to ASI year amount increases. The new model is less “binary” in the sense that it gives lower probability to very fast or very slow takeoffs. This is because the AI Futures Model models increases in the compute supply.25

The reason the AI Futures Model gives a lower chance of fast takeoffs is primarily that we rely on a new framework for estimating whether there’s an SIE and how aggressive it is.

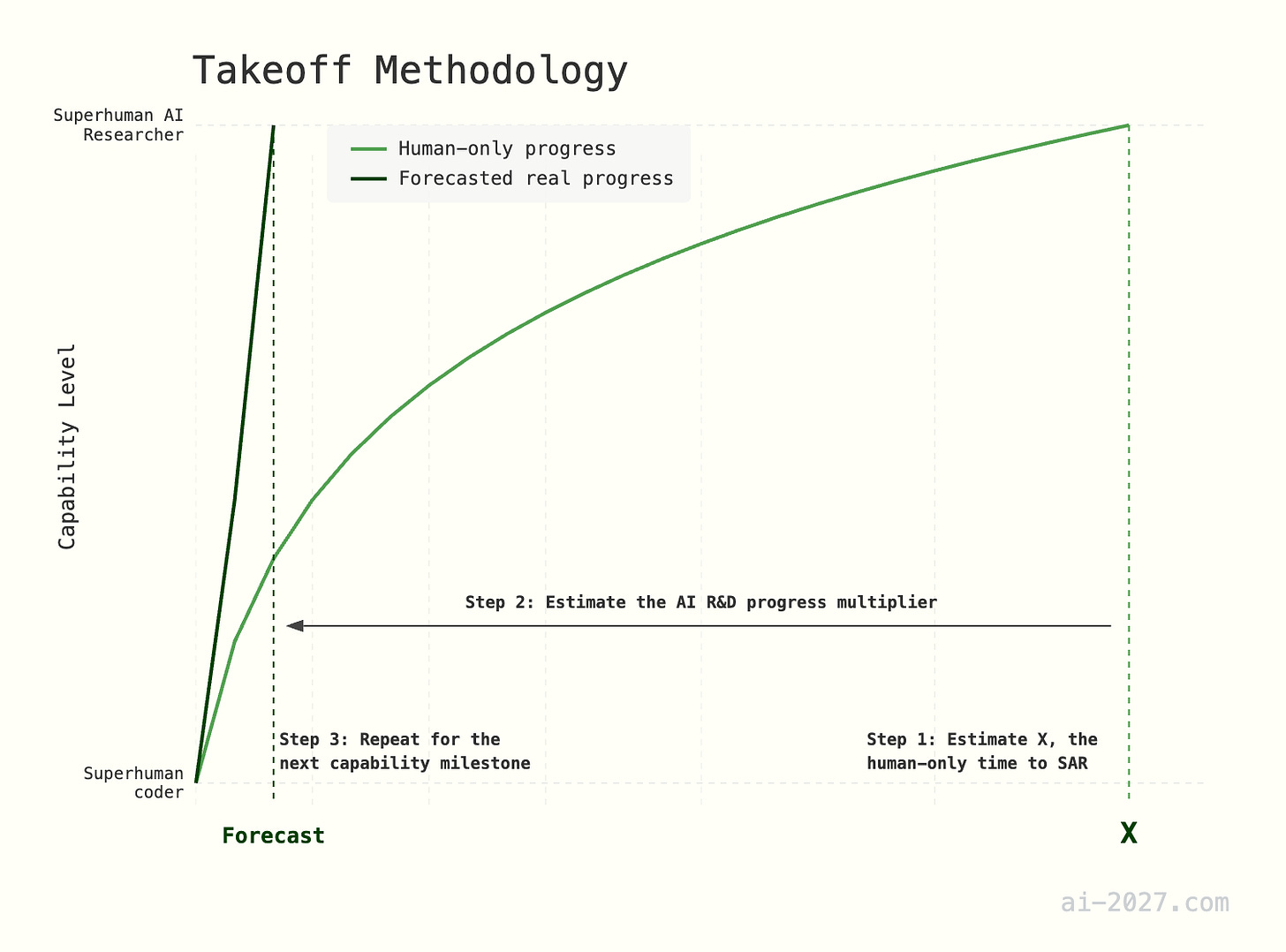

Our AI 2027 takeoff model predicted the progression of capabilities post-SC. Its methodology was also fairly simple. First, we enumerated a progression of AI capability milestones, with a focus on AI R&D capabilities, though we think general capabilities will also be improving. Then, for each gap between milestones A and B, we:

Human-only time: Estimated the time required to go from milestone A to B if only the current human labor pool were doing software research.

AI R&D progress multiplier (what we now call AI software R&D uplift, or just AI R&D uplift): Forecasted how much AI R&D automation due to each of milestones A and B will speed up progress, then run a simulation in which the speedup is interpolated between these speedups over time to get a forecasted distribution for the calendar time between A and B.

In order to estimate some of the human-only time parameters, the AI 2027 takeoff forecast relied on a parameter it called r, which controlled the diminishing returns to AI R&D. It was crudely estimated by backing out the implied r from the first human-only time requirement, which was to get from SC to SAR.

The AI 2027 model assumed that there were no compute increases; under this assumption, if it r>1 then successive doublings of AI R&D uplift (what we previously called progress multiplier) gets faster over time after full AI R&D automation. Others have referred to this possibility as a software intelligence explosion (SIE). In the model, each doubling took about 0.7x as long as the previous: we’ll call the ratio of successive uplift doublings b from here onward, i.e. b<1 means successive doublings are faster and we get an SIE.26

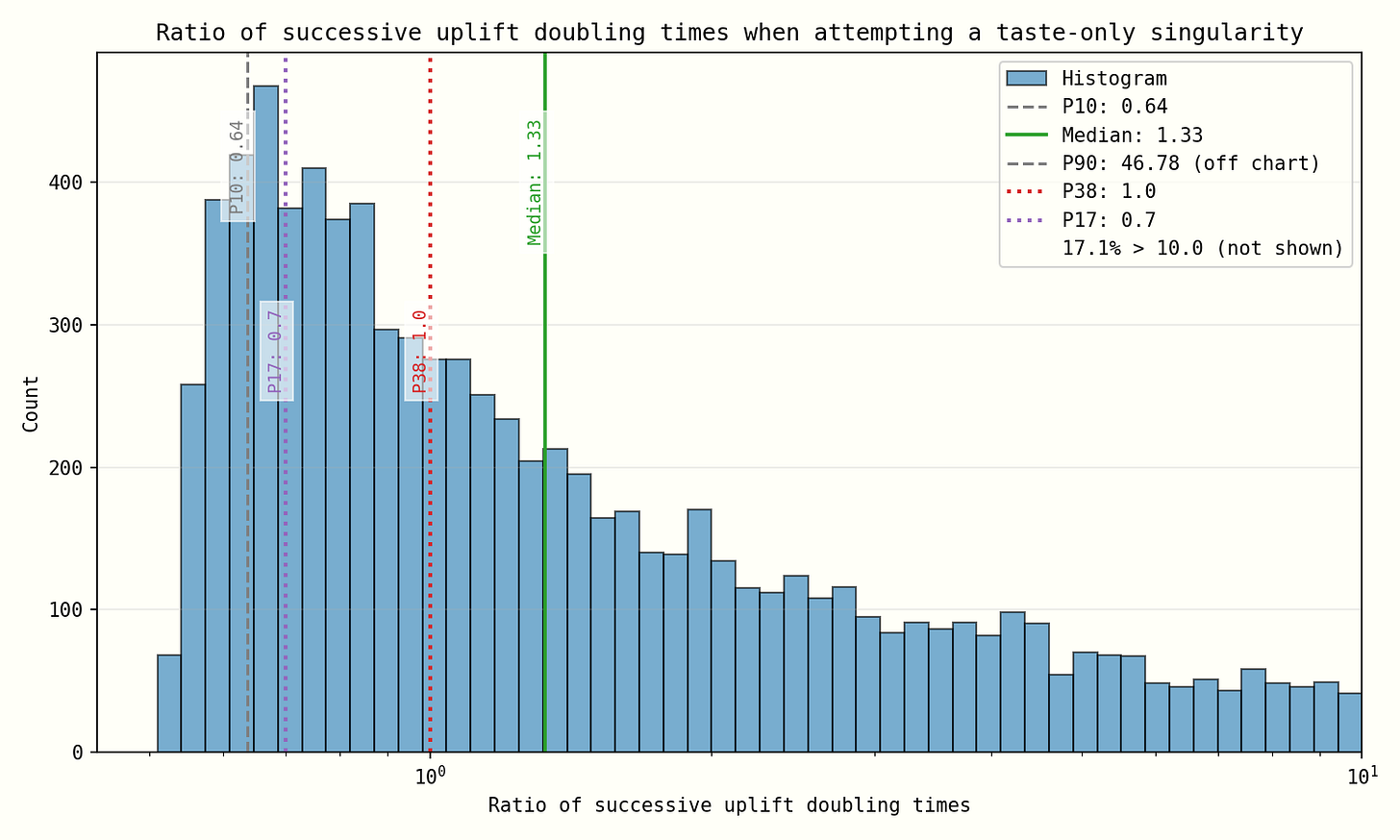

In the AI Futures Model, the condition for an SIE is more complicated because we model multiple types of AI R&D; we also include compute increases, departing significantly from the behavior of an SIE. That said, there is a similar understandable concept in our model: a taste-only singularity (TOS). This is the situation in which after full AI R&D automation and with only research taste improvements (no extra coding or compute), successive doublings of AI R&D uplift get faster over time. To make the analysis much simpler, we also ignore the limits of intelligence in our analysis; these usually don’t greatly affect the takeoff to ASI, but they do slow progress down somewhat.

Under these assumptions, we can define a similar b to that analyzed in an SIE.

We estimate b by combining the following parameters:27

(a) the ratio of top to median researchers’ value per selected experiment

(b) how quickly AIs improve at research taste as effective compute increases

(c) the rate at which software R&D translates into improved software efficiency (intuitively, the rate at which ideas are getting harder to find).

When using this framework, we get a less aggressive result (with our median parameters). Given that (a) was explicitly estimated in the AI 2027 model, and that we have a fairly aggressive estimate of (c) in the new model, implicitly most of the difference in results is coming from (b), how quickly AIs improve at research taste. We estimated this in our new model by looking at historical data on how quickly AIs have moved through the human range for a variety of metrics (more on that here).

With the AI 2027 model’s median parameters, each successive doubling of uplift took roughly 66% of the length of the previous (i.e. b=0.7).28 The AI Futures Model’s distribution of b is below.

In the AI Futures Model’s median case, there isn’t a TOS: each doubling would take 20% longer than the previous if taste were the only factor.29 But we have high uncertainty: 38% of our simulations say that successive doublings get faster, and 17% are at least as aggressive as the AI 2027 model (i.e. b<0.7).30

Remember that unlike the AI 2027 model, the AI Futures Model models compute increases; also in practice coding automation contributes some to takeoffs.31 Therefore, at similar levels of the bs we’ve defined here, takeoff in the AI Futures Model is faster.

Faster takeoffs are also correlated in our model with shorter timelines: when we filter for simulations that achieve SC in 2027, 35% of them have a b lower than the AI 2027 model’s median parameters. This is because some parameters lead to larger effects from automation both before and after SC, and furthermore we specified that there be correlations between parameters that govern how quickly coding abilities improve, and how quickly research taste abilities improve. We discuss this correlation in our results analysis.

For further analysis of the differences between our AI 2027 and new takeoff models, see our supplementary materials.

AGI stands for Artificial General Intelligence, which roughly speaking means AI that can do almost everything. Different people give different definitions for it; in our work we basically abandon the term and define more precise concepts instead, such as AC, SIAR, TED-AI, etc. However, we still use the term AGI when we want to vaguely gesture at this whole bundle of concepts rather than pick out one in particular. For example, we’ve titled this section “AGI timelines…” and the next section “Post-AGI takeoff…” because this section is about estimating how many years there’ll be until the bundle of milestones starts to be reached, and the next section is about estimating what happens after some of them have already been reached.

2047 for “unaided machines outperforming humans in every possible task”, and 2116 for “all human occupations becoming fully automatable.”

Some have also done extrapolations of Gross World Product, such as David Roodman’s Modeling the Human Trajectory.

More details:

Hans Moravec predicted human-level AI by 2010 for supercomputers and 2030 for personal computers in 1988, later revising to 2040 in 1999, with machines far surpassing humans by 2050.

Ray Kurzweil predicted in 1999 that AI would achieve human-level intelligence by 2029 and has consistently maintained this specific timeline for over 25 years.

Shane Legg has maintained a remarkably consistent AGI prediction since 2001, assigning 50% probability to human-level AGI by 2028. He went on to found DeepMind and has not changed his timeline.

Technically, the report predicted the arrival of Transformative AI, or TAI, which was defined as having at least as big of an impact as the Industrial Revolution.

Rule of thumb inspired by Lindy’s Law: It’s reasonable to guess that a trend will continue for about as long as it’s been going so far. We wouldn’t dream of confidently extrapolating this trend for thirty years, for example. (We do in fact run the model into the 2050s and onward in our Monte Carlos, but we acknowledge that the probability of reality diverging dramatically from the model increases with the duration of the extrapolation.)

Peter Wildeford has a model which has the possibility of doublings getting easier or harder, but does not model AI R&D automation or changes to labor or compute growth.

GATE and the Full Takeoff Model also model the progression after full AI R&D automation, but neither of their authors claim that their model is intended to do it well.

These estimates are then shaded up to account for capability improvements at the same compute level in addition to efficiency improvements at the same performance level. This adjustment brings the methodology closer to ours, but still we think it’s helpful to focus specifically on research taste skills. And finally, in Davidson and Houlden, everything is converted to the units of gains in the number of parallel workers, which we view as a much less natural unit than research taste quality.

Among other advantages of having an integrated model: our model itself already bakes in most of the various adjustments that Davidson and Houlden did ad-hoc to their estimate of r, and we can generally ensure reasonable starting conditions (as opposed to Davidson and Houlden’s gradual boost).

Our model operationalizes AC as follows: An AC, if dropped into present day, would be as productive on their own as only human coders with no AIs. That is, you could remove all human coders from the AGI project and it would go as fast as if there were only human coders. The project can use 5% of their compute supply to run ACs.

See especially this Anthropic survey of researchers claiming >100% productivity improvements, but also this METR uplift study which found that people systematically overestimate the amount of uplift they were getting from AI assistance.

That is, if we think that eventually there will be an AI system which outperforms humans at all horizon lengths, then that means the trend must shoot to infinity in finite time.

That is, the part of our model that deals with AI timelines, i.e. the length of the period leading up to the “automated coder” milestone, centrally involves the METR trend. After that milestone is reached, horizon length continues to increase but isn’t directly relevant to the results. The results are instead driven by increases in automated research taste and coding automation efficiency.

Our model operationalizes SAR as follows: if dropped into an AGI project in present day, a SAR would be as good at research taste as if there were only human researchers, who were each made as skilled as the top researcher.

In our model, the SAR’s compute budget is 1% of the company’s compute. The SAR must also qualify as an automated coder (AC), i.e. be able to fully automate coding at the AGI project with 5% of its compute budget (an AC has a higher compute budget because more human labor is currently spent on coding than experiment ideation/selection).

Our operationalization is the same as what we defined as a superhuman AI researcher (SAR) from our previous work, except that it only needs to match the productivity of the project’s best researchers, rather than the project’s best researchers sped up by 30x and 30x more numerous. We also separate out research taste from coding.

What do we mean when we say that the gap between a top human researcher and SIAR is 2x greater than that between the median and top human researcher? We mean the following. First, let’s define a transformation between AIs’ capability level b and a number of SDs relative to the median as:

Assume that we can infinitely sample from the process that produced the relevant human population, in this case the human researchers at the AGI project. For example, we could imagine sampling from parallel Earths.

Look up what percentile p the AI has within this population, based on its capability level b.

An AIs’ SDs relative to the median, s, is equal to the inverse normal CDF of p.

Now, using s as the result of applying the process above, define a SIAR as reached when (s_siar - s_top_human) = 2 * (s_top_human - s_median_human). A SIAR has the same budget constraints as a SAR, and must also meet the requirements for an AC.

Our model operationalizes TED-AI as follows: A TED-AI is an AI system that could, if dropped into the present day & given the resources of a large tech company & three months to prep, fully automate 95% of remote work jobs in the US. It need not be able to do all 95% at the same time (perhaps there isn’t enough compute to run enough copies of the TED-AI for that), but it needs to be able to do any 10% of them using only 50% of the US’s AI-relevant compute.

Our model operationalizes ASI as follows: An ASI would, if dropped into present day & given the resources of a large tech company & three months to prep, be able to fully automate 95% of remote work jobs in the US to the level where it is qualitatively 2x as much above the best human as the best human is above the median professional. Also, here we define “the median professional” not as the actual median professional but rather as what the the median professional would be, if everyone who took the SATs was professionally trained to do the task. (We standardize the population that is trained to do the task because otherwise the ASI requirement might be quite different depending on the population size and competence levels of the profession. See above regarding how we define the 2x gap.)

Spot-checking in our model: Serial coding labor multiplier is basically the square root of parallel coding labor multiplier, and so when I look at my default parameter settings at the point where serial coding labor multiplier is ~10x (May 2030) the AIs have research taste equivalent to the median AI company researcher. Sounds about right to me.

I’ve talked about this elsewhere but I generally think that if you don’t like using a superexponential and insist on an exponential, you need to come up with a different interpretation of what it means for a model to have horizon length X, other than the natural one (“A model has horizon length X iff you are better off hiring a human for coding tasks that take humans much longer than X, but better off using the model for coding tasks that take humans much less than X.”) Because on that interpretation, an exponential trend would never get to a model which outperforms humans at coding tasks of any length. But we do think that eventually there will be a model which outperforms humans at tasks of any length. In other words, on the natural interpretation the trend seems likely to go to infinity in finite time eventually. You can try to model that either as a smooth superexponential, or as a discontinuous phase shift… even in the latter case though, you probably should have uncertainty over when the discontinuity happens, such that the probability of it happening by time t increases fairly smoothly with t.

For example, I want to think more about serial speed bottlenecks. The model currently assumes experiment compute will be the bottleneck. I also want to think more about the software-only-singularity conditions and whether we are missing something there, and square this with soft upper bounds such as “just do human uploads.”

Note that with the new model, we’ve moved toward using Automated Coder (AC) as the headline coding automation milestone, which has a weaker efficiency requirement.

That said, we note that the benchmarks and gaps version had longer median SC timelines (Dec 2028). And Eli’s all-things-considered SC median was further still in 2030, though Daniel’s was 2028.

That said, we still think that the AI Futures Model gives too low a probability of <10 year takeoffs, because we are not modeling growth in compute due to hardware R&D automation, hardware production automation, or broad economic automation.

As discussed here, the AI 2027 model set r=2.77 and 1.56 at different points. b=2^(1/r-1), so b=0.64 to 0.78.

2^((0.315/0.248)-1). See the justification for this formula on our website.

Note that the minimum b in our model is 0.5. This is a limitation, but in practice, we can still get very fast takeoffs. For example, if b were 0.5 and didn’t change over time, this would lead to a finite-time singularity in 2 times longer than the initial uplift doubling time.

This could also be influenced by the uplifts being different for different milestones, or other factors. Unfortunately we haven’t had a chance to do a deep investigation, but a shallow investigation pointed toward compute increases being the primary factor.

One other question: In the median case, in a year, when we have the data from 2026, should we expect the uncertainty in the time to an automatic coder go down, and, typically, by how much?

Impressive modeling depth on the AI R&D automation dynamics. The shift from 2027 to 2031 median for AC based on more conservative pre-automation speedup estimates feels intellectualy honest. I ran into smiliar issues when modeling capability curves last year where the interpolations between present and endpoint gave way too optimsitic midpoints. The METR-HRS extrapolation approach beats bio anchors but totally agree the trend could break or the horizons might not translate cleanly to realworld automation value.